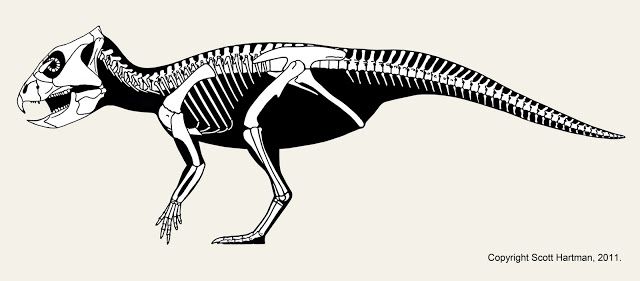

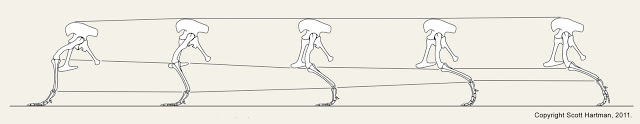

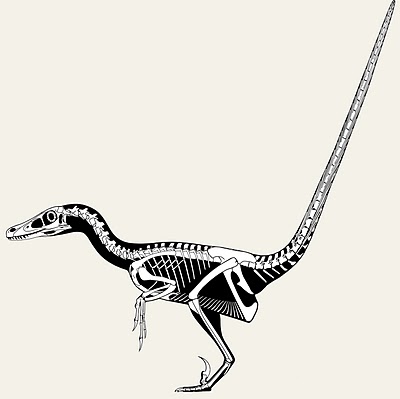

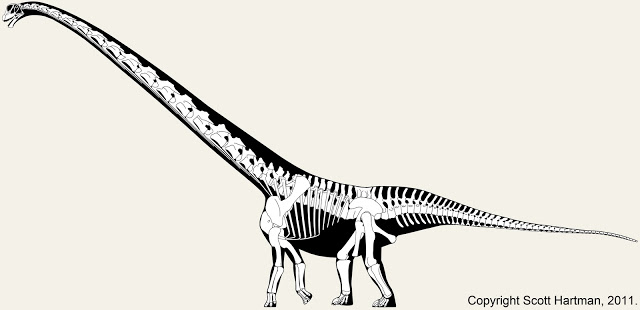

What is particularly noteworthy is that the two distal vertebrae were not known when I first made this diagram. We only had ~10% of the tail, but with careful scaling and proper selection of taxa to model the bones on, I didn't have to make any changes to the skeletal after the additional bones were excavated and prepared.

Obviously things don't always work out this well - sometimes it's less clear which taxa should be used to constrain missing elements, or an animal might have truly novel proportions. But missing data and margins of error are simply a fact of life in paleontology. What I hope is clear is that regardless of the possibility for error, this skeletal is intended to be a realistic portrayal of the animal, not a purely schematic one.

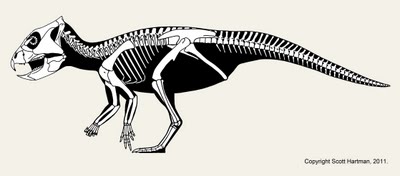

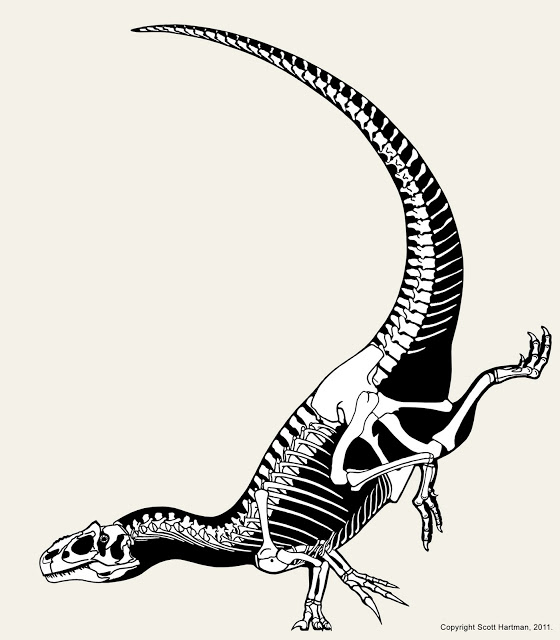

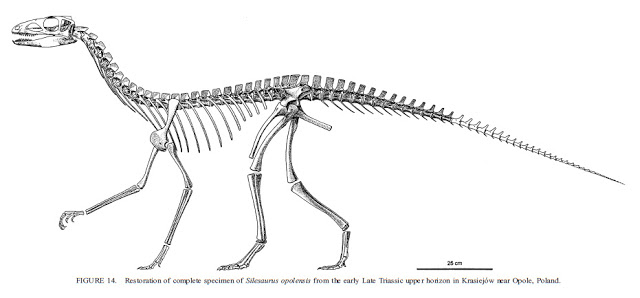

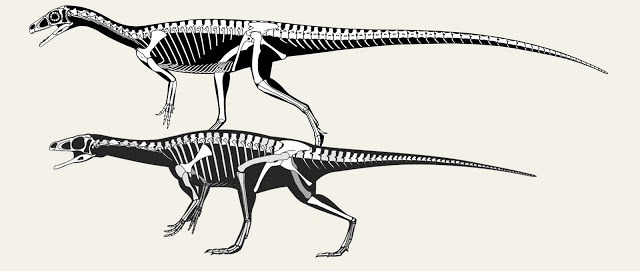

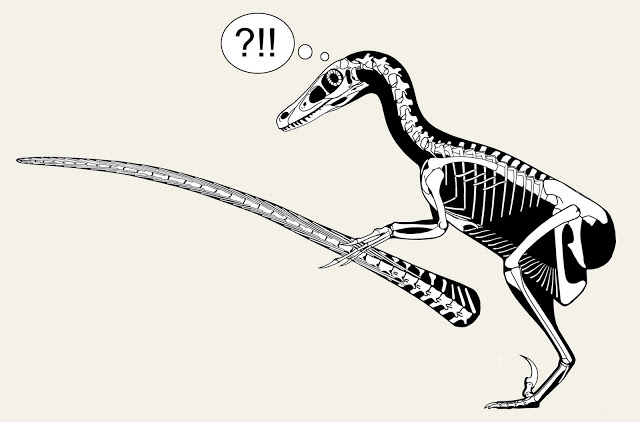

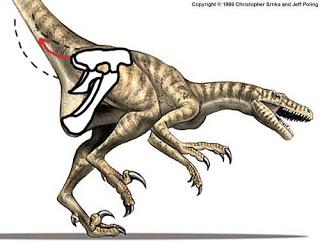

While the degree to which a skeletal drawing is schematic or realistic isn't always black and white, the impact they have on paleo art is. When an artist bases a life reconstruction on a skeletal they need to have the real proportions and shape of the animal, which are just not available in schematic skeletal diagrams. And it's not just art - for better or worse researchers sometimes cull data such as relative limb proportions from published skeletal drawings. If, for example, a researcher was interested in comparing relative tail lengths in basal dinosaurs, it would matter very much which skeletal of Panphagia was evaluated.

For some dinosaurs only a single skeletal reconstruction exists. Sometimes when when there are two or more they are quite different. So how is one to know which (if any) of the skeletals are meant to be more literal, and which are schematic? This brings me to the main issue of the day:

We need more transparency in skeletal drawing labels!

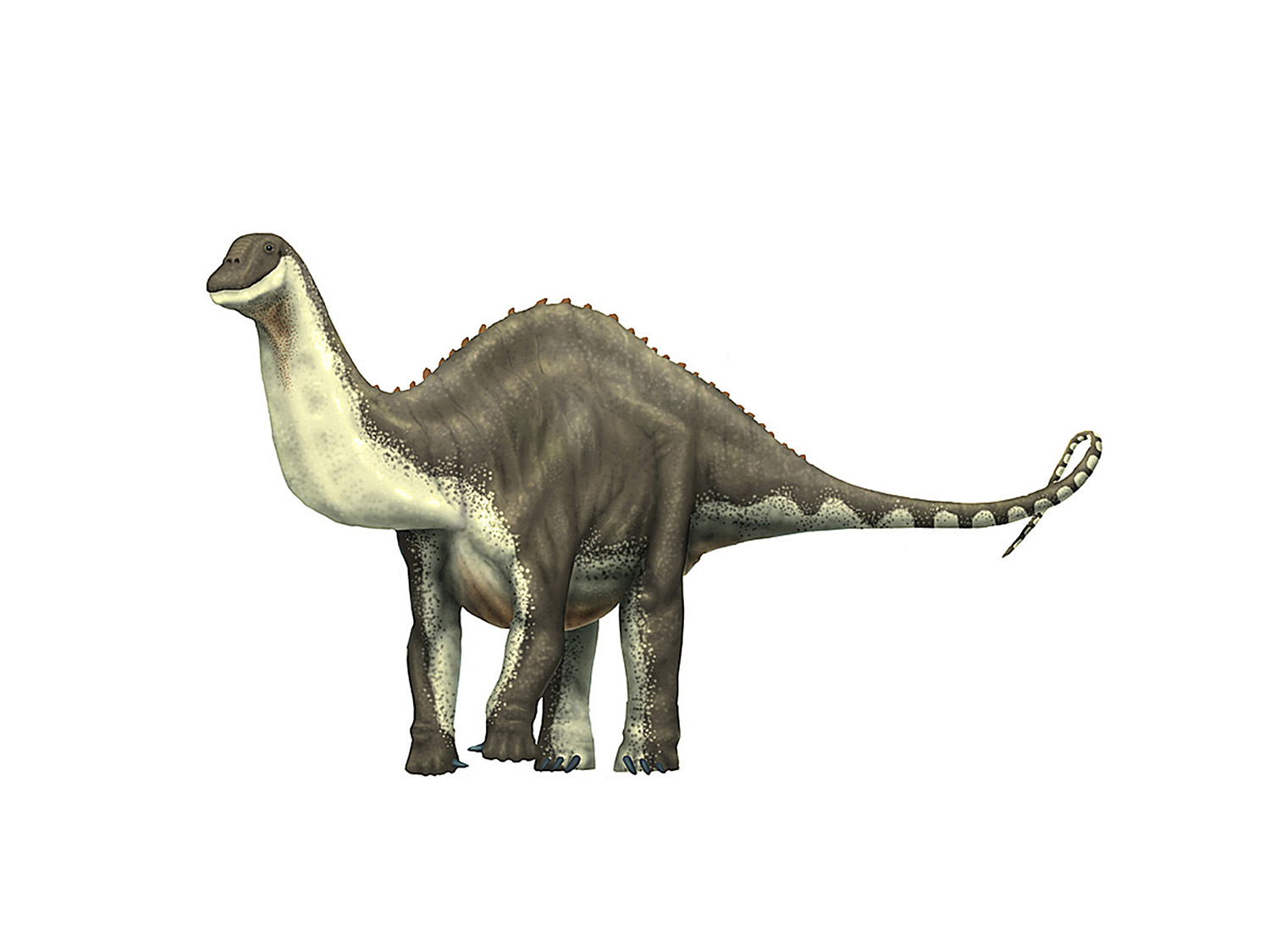

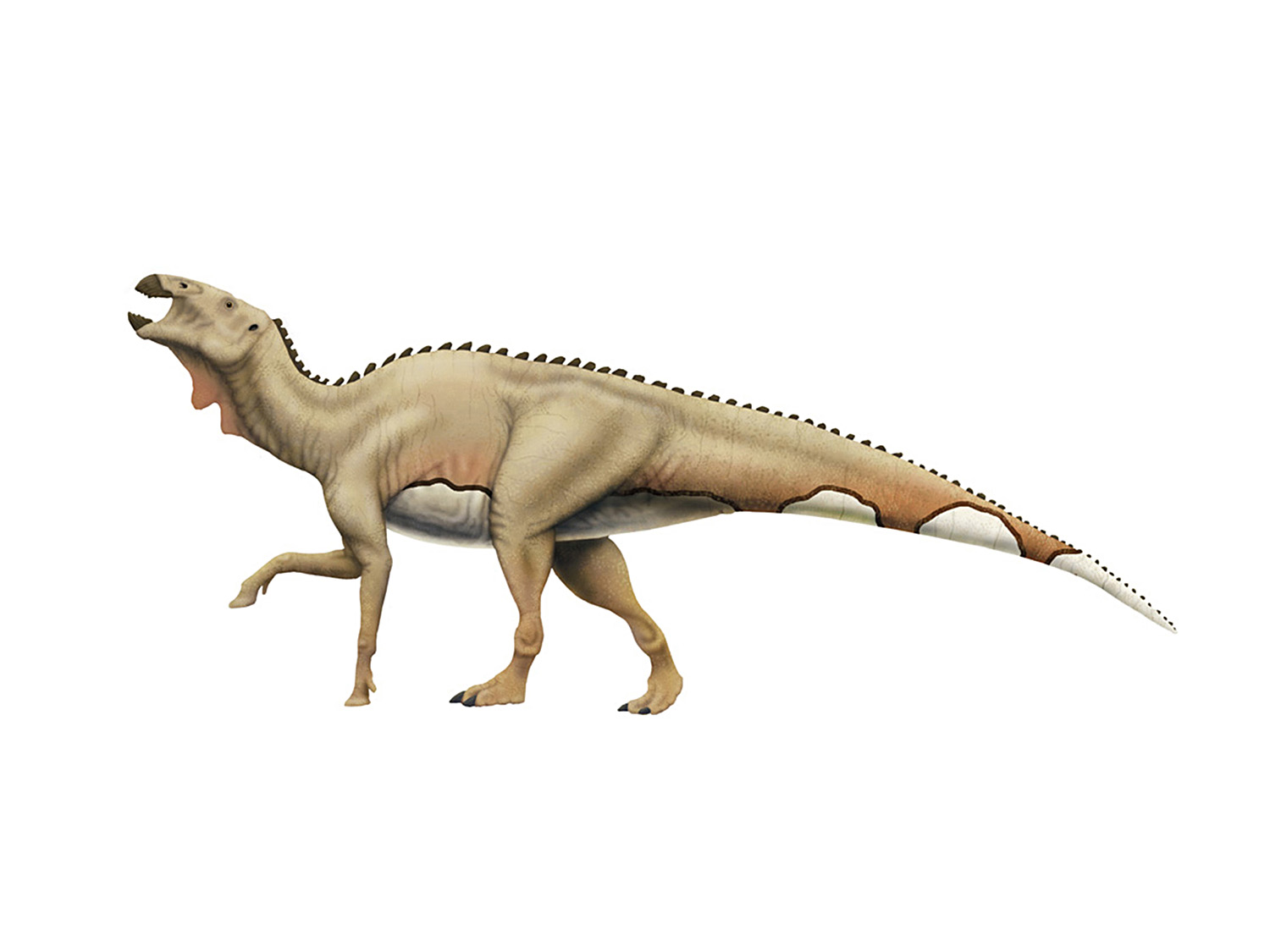

The two drawings of Panphagia at the beginning of this post are quite different (especially if you are trying to draw the beast), yet they both convey accurate and useful information. They just aren't intended to convey the same types of information (although there is overlap). When writing a professional paper, which one of these styles is "better" depends on the needs of the authors, the time, ability, and access to the data that the illustrator has, and a host of other practical concerns. Far be it from any of us to dictate that one type of skeletal diagram is suitable in all cases.

What is needed is for authors (and their scientific illustrators) to label their skeletal diagrams more precisely. Skeletal drawings are not like the schematic diagrams of stratigraphic columns, as there are large bodies of published skeletal diagrams that are intended to be realistic portrayals. Because there are multiple visually similar types of skeletal diagrams, we need proper labeling so that the viewer's expectations match the authors' intent.

Proper labeling is a basic part of science; papers are rightly rejected for not documenting the confidence interval in a study, or for failing to be precise in the use of significant figures. In fact most of these practices become second nature long before getting a graduate degree. So why not with skeletal drawings?

There actually are a few stumbling blocks. For one, there aren't any published guidelines to differentiate between the two. Another problem is that not all authors are actually aware of the difference - I know of cases where the artist has been largely left to produce a skeletal on his or her own with little instruction ("it's like taxon A but with a bigger nose and longer tail"). Yet other researchers simply don't think any extinct animal can be reconstructed with this degree of accuracy ("too many assumptions") so they feel all skeletal reconstructions are schematic. This last view may not be correct, but many of the techniques that render it incorrect are not published in a peer-reviewed journal.

But that doesn't mean we can't start to work to make it better. To facilitate this (or at least a healthy discussion) I will make the following suggestions for researchers and illustrators:

For researchers:

1) No matter how talented an illustrator, people cannot consistently render accurate proportions without measurements. If measurements are not available (or not made available) the diagram must be assumed to be schematic.

2) People can (obviously) not draw accurate bone profiles if they have never seen the bones in question. Ideally an illustrator would see the original material, but if this isn't practical be sure to get photos, the more the merrier. If this is also not practical, label the skeletal diagram as schematic.

3) Sometimes there just are not enough bones to justify a new skeletal reconstruction, so skeletals of related animals are modified just enough to show of the new bone (or bones). Please label them "Schematic skeletal of Taxon A, modified after Smith (2010)".

4) Remember there is no more shame in using a schematic skeletal diagram then there is in using a strat column. But please label the convention you are using!

5) If a skeletal is intended to be a realistic reconstruction of the animal, then it should also be treated as a form of data that needs updating. If new finds or a more complete description uncovers some inaccuracy, update/amend the image it in a future publication, as you would with a description or phylogenetic analysis.

For Illustrators:

1) Ask up front what sort of skeletal drawing is being asked of you. You should also know what you need in order to produce the requested image - if you don't have enough information to produce the type of drawing that is desired, ask for it.

2) Illustrations are often used outside of professional papers - in books, museum displays, on this fancy world wide web thingy. Maintain proper labeling wherever possible (I realize that illustrators may have little control over some projects, but maintain best practices whenever possible - this will also encourage book editors and museum directors to adopt more explicit labels).

3) If you are producing a realistic skeletal reconstruction, take responsibility for updating it as necessary. If there isn't time to make changes, put that in the label (e.g. "Executed before additional information about the elongated neural spines was available.")

4) There's no shame in making a schematic diagram. It's a useful contribution to science, so don't feel like you're producing a "second class citizen" of the illustration word and decide to not label it precisely.

5) Finally, if you are trying to do a life reconstruction of a dinosaur, be sure to find out if the skeletal drawing available to you is schematic or not. If it is, you may need to do more work before illustrating it. That is, unfortunately, the nature of our work.

Conclusions?

I feel like this issue has been a "dirty little secret" in both scientific and paleo art circles. Hopefully this provides some food for thought. A lot of work needs to be done if we're going to continue to move the "science" in scientific illustration forward, but more accurate labeling of images should be something that can be universally embraced, and something we should all be aware of.

* I want to be very clear that I'm not criticizing the illustrator of the original Panphagia skeletal reconstruction (there isn't specific credit given in the Martinez & Alcober paper, so I presume it was done by one of the authors). It's a perfectly good schematic, and demonstrates the key features of Panphagia as well as which bones are preserved. This also in no way should cast aspersions on the paper itself, which is an excellent example of the value of publishing longer format descriptions in journals like PloS ONE, rather than the glorified abstracts required by certain high impact journals.

I chose this example because it was recent enough and high profile enough to make an excellent jumping off point for the larger discussion of schematic skeletals, not because there is anything wrong or unusual about it.