A History of Skeletal Drawings: Part 3 - Dino Renaissance to the present

/

We saw in Part 2 that the modern convention of skeletal illustration had largely been invented by the 1950s. Alas, it didn’t immediately catch on like wildfire, and in other ways the 1950s represents a nadir in terms of published skeletals. Yet starting in the 1960s would see steady progress up to the modern era. How did it all happen? Let’s take a look!

Dinosaur Renaissance, Skeletal Evolution:

Most accounts of the Dinosaur Renaissance start in the late 1960s. And it’s true that this period saw rapid change in the peer-reviewed literature on dinosaur biology; John Ostrom, Robert Bakker, Peter Galton and others helped drive a period of time that saw paleontologists unite dinosaurs back into a single evolutionary group, add birds to that group, and re-evaluate the metabolism and growth rates of dinosaurs. Certainly the renaissance witnessed a push to make dinosaur reconstructions more accurate, and a revival of interest in functional morphology. Yet the seeds of that change were sown in the early 1960s.

Of course scientific ideas also have historical backdrops. Ostrom is generally credited with ushering in the idea of endothermic dinosaurs with his 1969 paper (enticingly titled: Terrestrial vertebrates as indicators of Mesozoic climates). Yet it was preceded by papers by L. Russell (1965), Currey (1965), and Wieland (1942), all discussing endothermic dinosaurs. Not that their work diminishes the impact that Ostrom and other architects of the modern era had in the 1970s, but as both scientists and scientific illustrators it behooves us to always be aware of context. So let’s jump back to see the beginning of the skeletal renaissance:

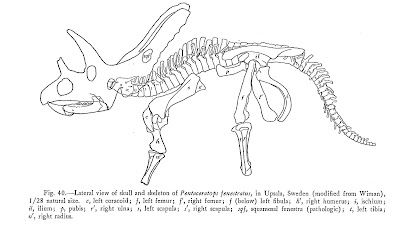

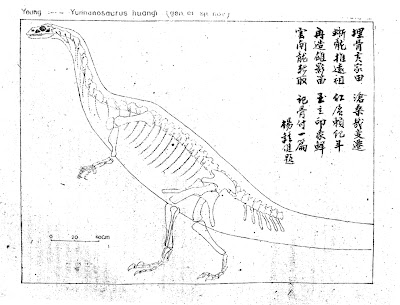

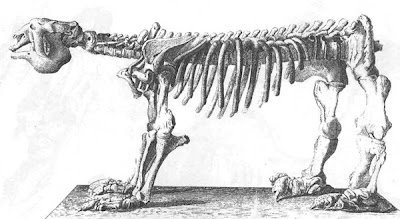

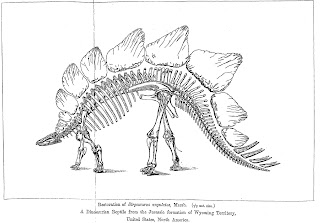

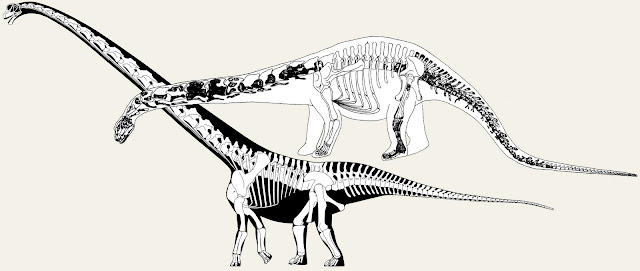

(Young's 1954 Mamenchisaurus. Not real renaissance-y.)

Much of the worlds' economy was recovering nicely in the post-war era, and the world had just seen its first black-silhouetted skeletal drawings. Yet there seems to have been a general malaise in the realm of dinosaur reconstructions in the 1950s. Professor Young continued to push out an outlined skeletal or two, but if anything his outlines seemed to get less accurate as time wore on. By 1960 he dropped the convention altogether in his description of Shansisuchus.

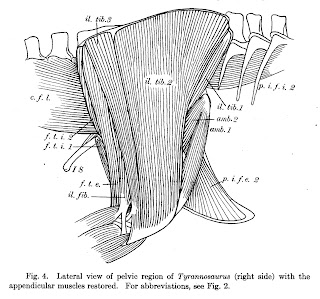

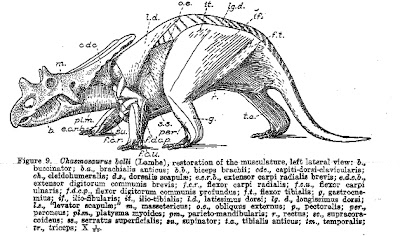

Young’s example is in many ways symbolic of the problems that plagued the field. There were no current anatomical guidelines for producing soft-tissue outlines; earlier attempts by Romer and others to reconstruct muscles were ignored or forgotten. Even the articulation of major skeletal elements varied between researchers without apparent rhyme or reason. In short, there was implicit cynicism about even attempting scientific rigour with skeletal reconstructions.

(So Young to be so cynical!)

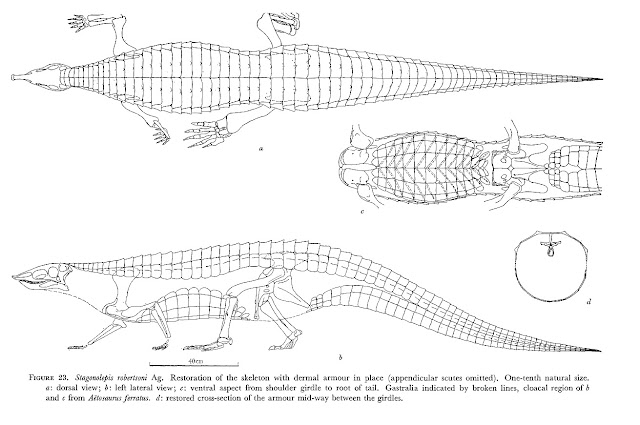

The 1960s brought the beginnings of revolution. Not the flower-powered one you may be thinking of, but anatomical reconstructions that deserve our admiration and respect. The first (and perhaps most overlooked) of the proto-renaissance workers was Alick Walker. Often maligned due to his stance on bird origins, Walker was a true comparative anatomist, and took great effort in his descriptive monographs. He also happened to be an excellent scientific illustrator.

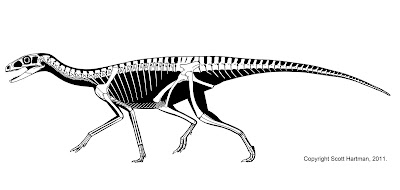

When he published his dissertation on Stagonolepis it contained not one, but two multiple view skeletal reconstructions, demonstrating both the anatomy and the armor of the aetosaur (armored one shown below). Perhaps even more importantly the text of the paper includes an entire section entitled "Reconstruction of the skeleton" in which he explicitly lays out the assumptions he worked from.

(Walker's 1961 Stagonolepis, an uncelebrated progenitor of the modern era)

In many ways this humble aetosaur is the first skeletal reconstruction of the modern era. Not because the anatomical details are unassailable, but because great care was taken to provide all of the relevant information for others to study and improve upon. And really, who doesn't like multi-view skeletal reconstructions?

Walker's career was typified by a small number long descriptive works, so his skeletal reconstructions were not great in number. He did produced a few more skeletals of note; his 1964 Ornithosuchus (while in a Godzilla pose) was well proportioned and fairly modern. He also continued the Huene/Wright school of schematic skeletal reconstructions for his Hallopus paper. This style of skeletal reconstruction was about to make a comeback, and it’s hard to imagine that Walker’s use of it wasn't influential.

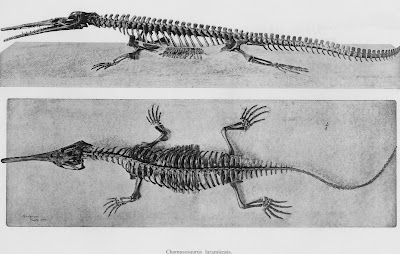

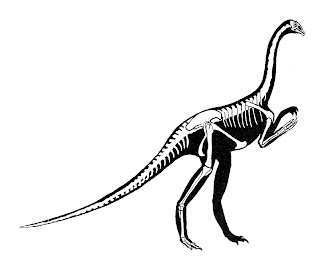

(Walker's 1970 Hallopus in the Walker/Wright style)

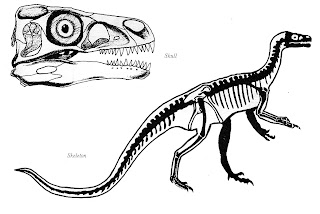

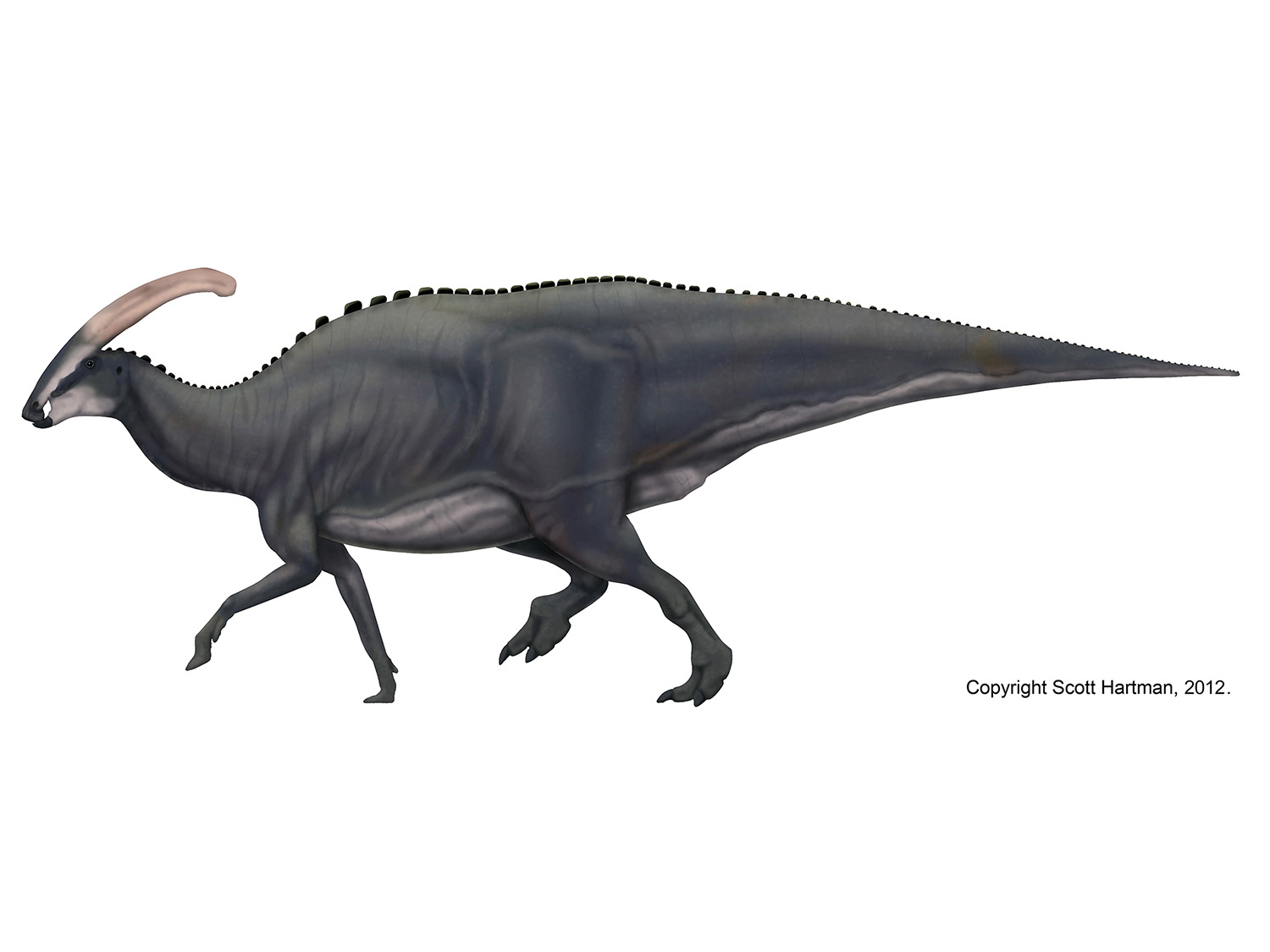

Of course Walker wasn’t the only one publishing archosaur papers in the 1960s. John Ostrom named a new species of Parasaurolophus in 1963, and Ewer’s monograph on Euparkeria provided a skeletal of a sprightly Euparkeria in a bipedal dash. Neither was as inspired as Walker’s reconstructions, but Ostrom's work was to have a larger impact on the public conscience in 1969, when a skeletal reconstruction of his new dromaeosaur was published:

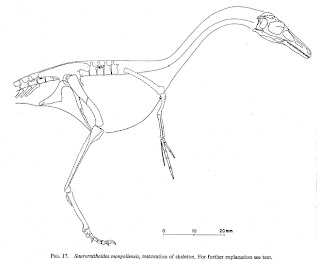

Ostrom's 1969 skeletal reconstruction of Deinonychus may have been inspired by his changing views on dinosaur metabolism, and its discovery is rightly seen as pivotal event in the Dinosaur Renaissance. But things were moving quickly now on the skeletal drawing front. 1969 also saw Dale Russell publish an excellent description (and skeletal reconstruction) of Troodon. The reconstruction was well proportioned, and he appears to have taken a page from the Huene/Wright/Walker playbook when he had to outline missing portions of the vertebral column.

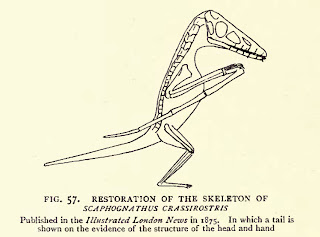

(Sure Russell's 1969Troodon looks nice, but how would it look with a giant head and lacking a tail?)

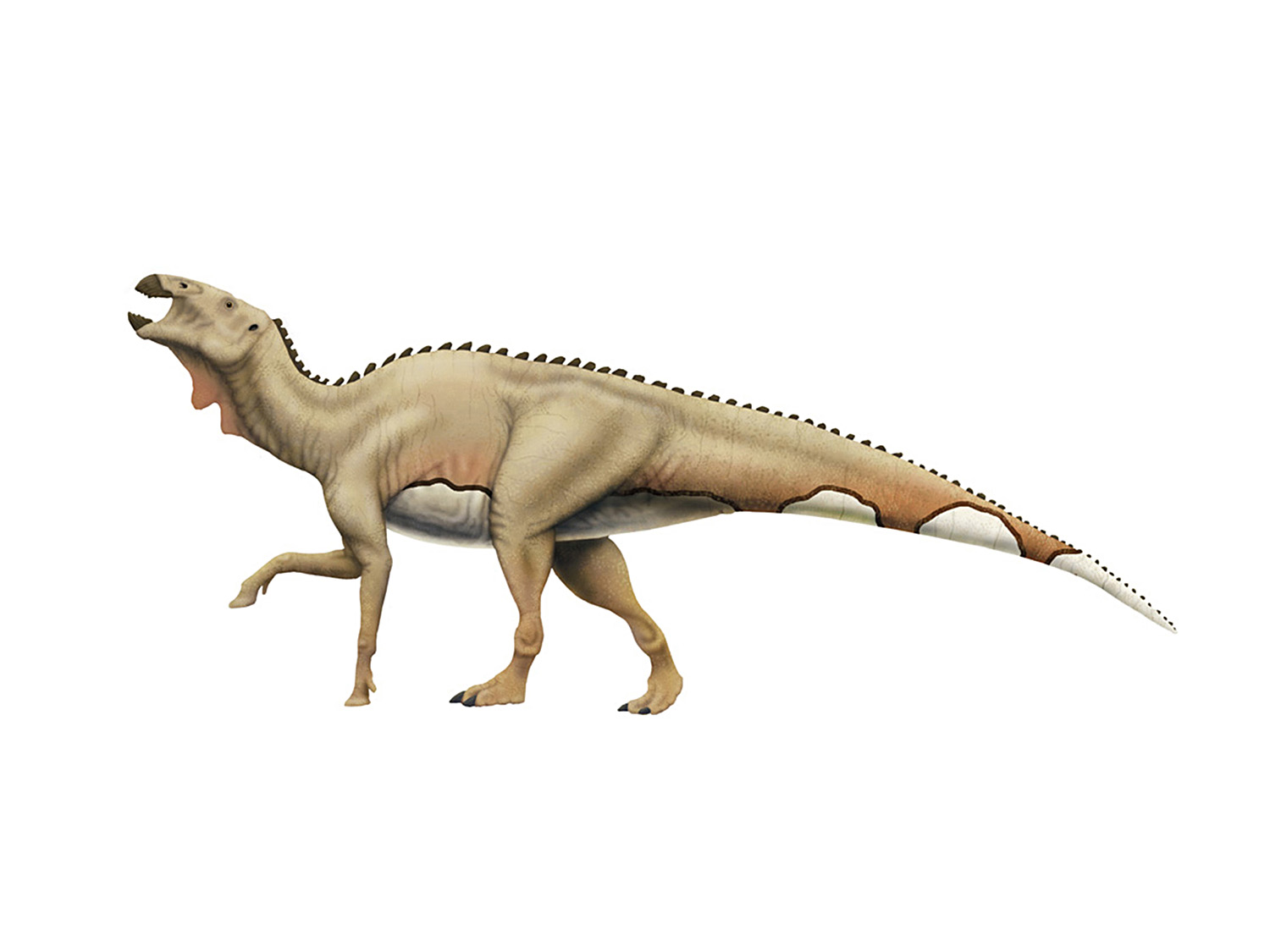

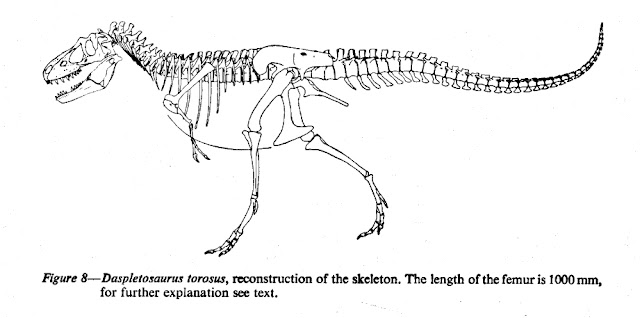

Dale Russell published several new skeletal reconstructions during the 1970s (and up till today), and they were excellent examples of an exciting new trend. In the past it was notable if a skeletal drawing got either the shape of the bones right, or the general proportions. Russell somehow managed to both provide accurate skeletal proportions and accurate representations of individual bones. If you compare Dale Russell’s Daspletosaurus to that of Greg Paul, you'll see that the the only substantive difference is that Russell arched the back up, while Paul arched his down (Greg is correct in this case).

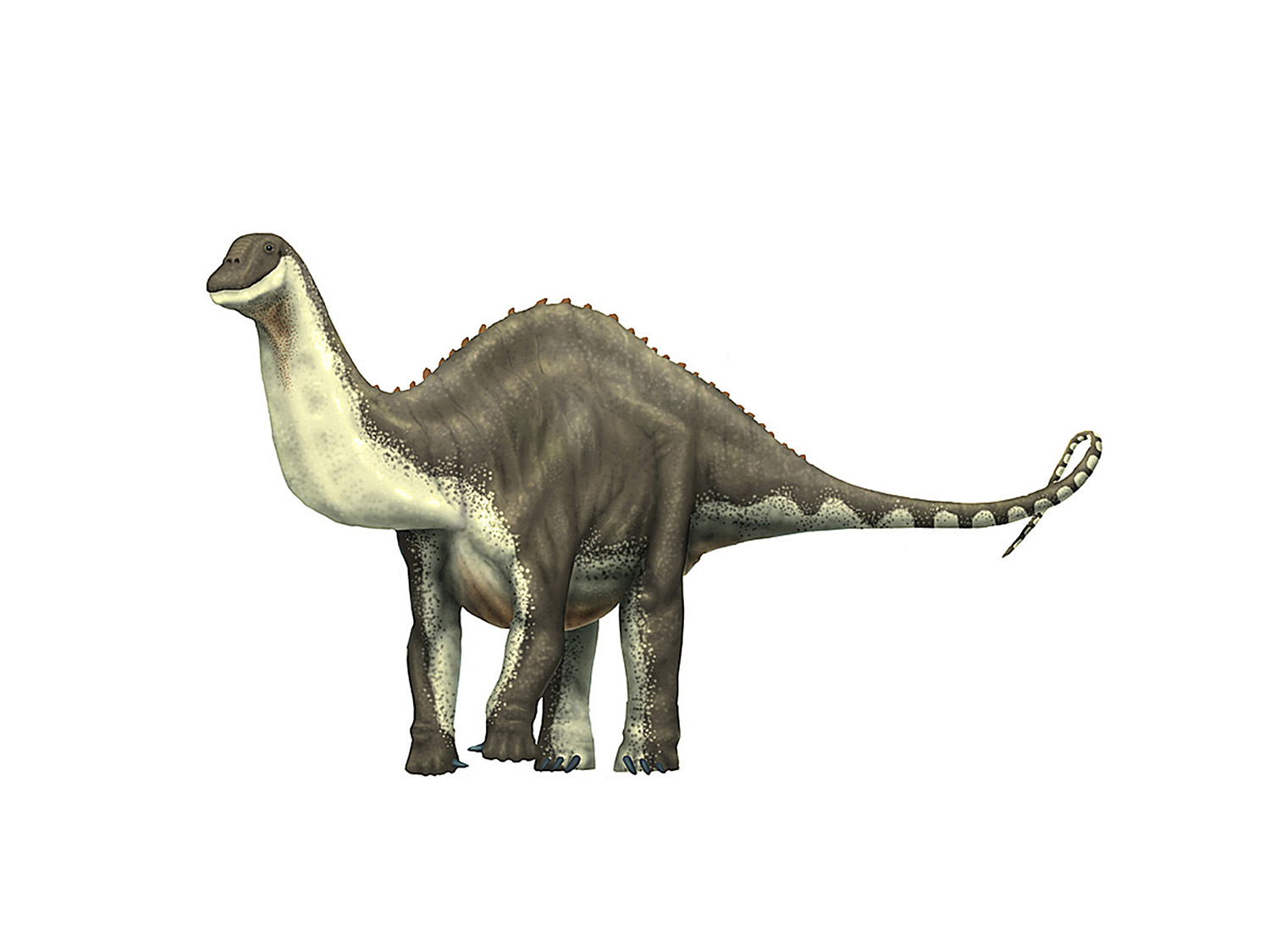

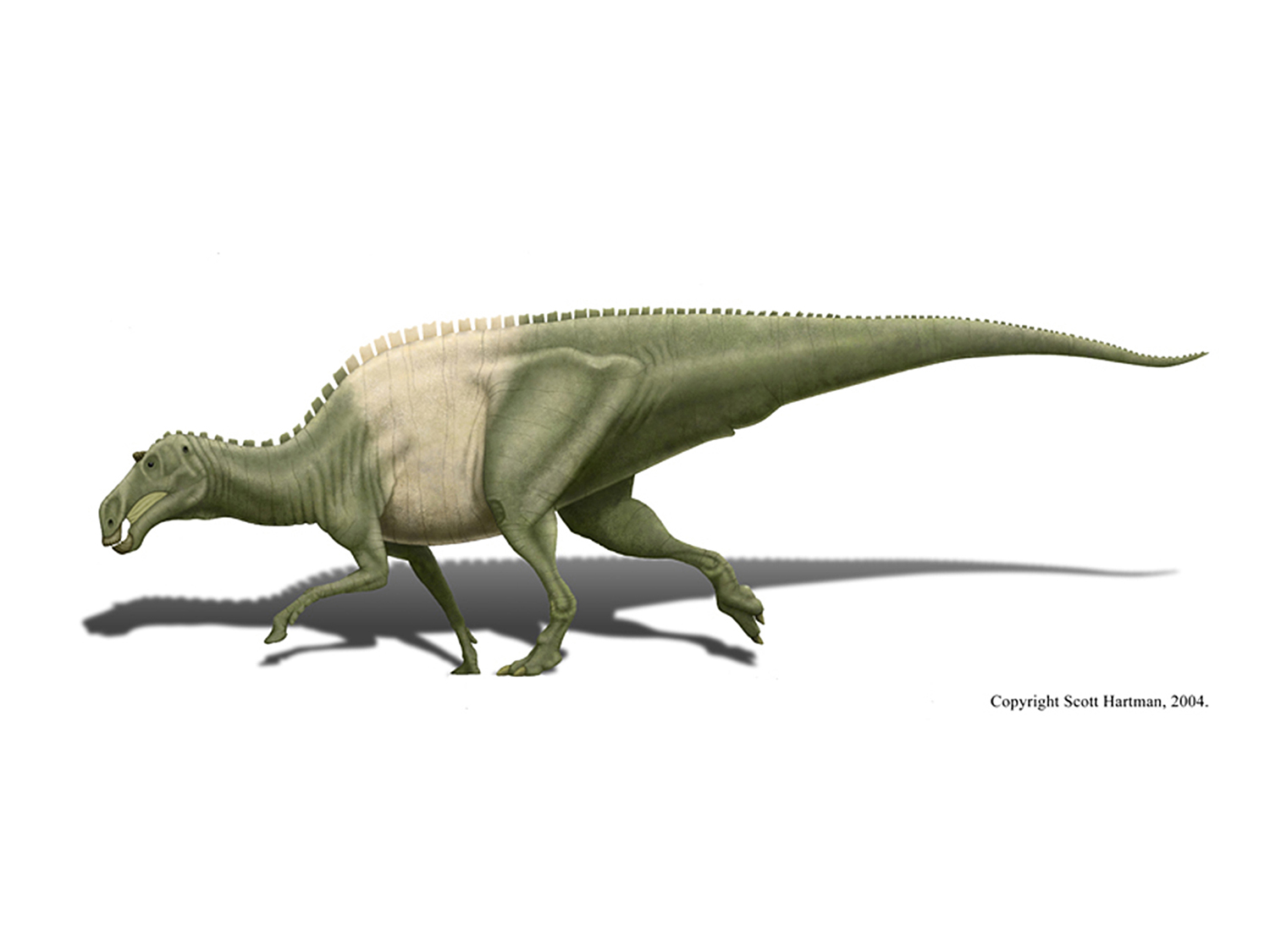

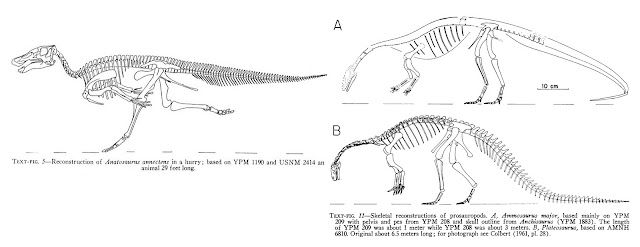

Hot on the heals of Dale Russell's debut, Peter Galton started a prolific career of skeletal reconstructions in 1970. Like Russell, his reconstructions were accurate at both capturing the general proportions of the skeleton, as well as the specific shapes of individual bones.

(Galton's 1970 Edmontosaurus and 1971 "prosauropods" are accurate in both proportion and detail. What a show off!)

Let's pause to catch our breath; Galton and Russell were producing some of the finest dinosaur skeletal reconstructions ever seen, Ostrom was finding crazy new theropods and stirring the pot on dinosaur energetics...honestly it feels like an embarrassment of riches were suddenly heaped upon dinosaur paleontology in the blink of an eye. Yet things were about to get kicked up a notch; Ostrom’s student (and frequent Galton collaborator) Robert Bakker published a series of papers - not to mention skeletal drawings - throughout the 1970s that really put the "Bam!" in the Dinosaur Renaissance

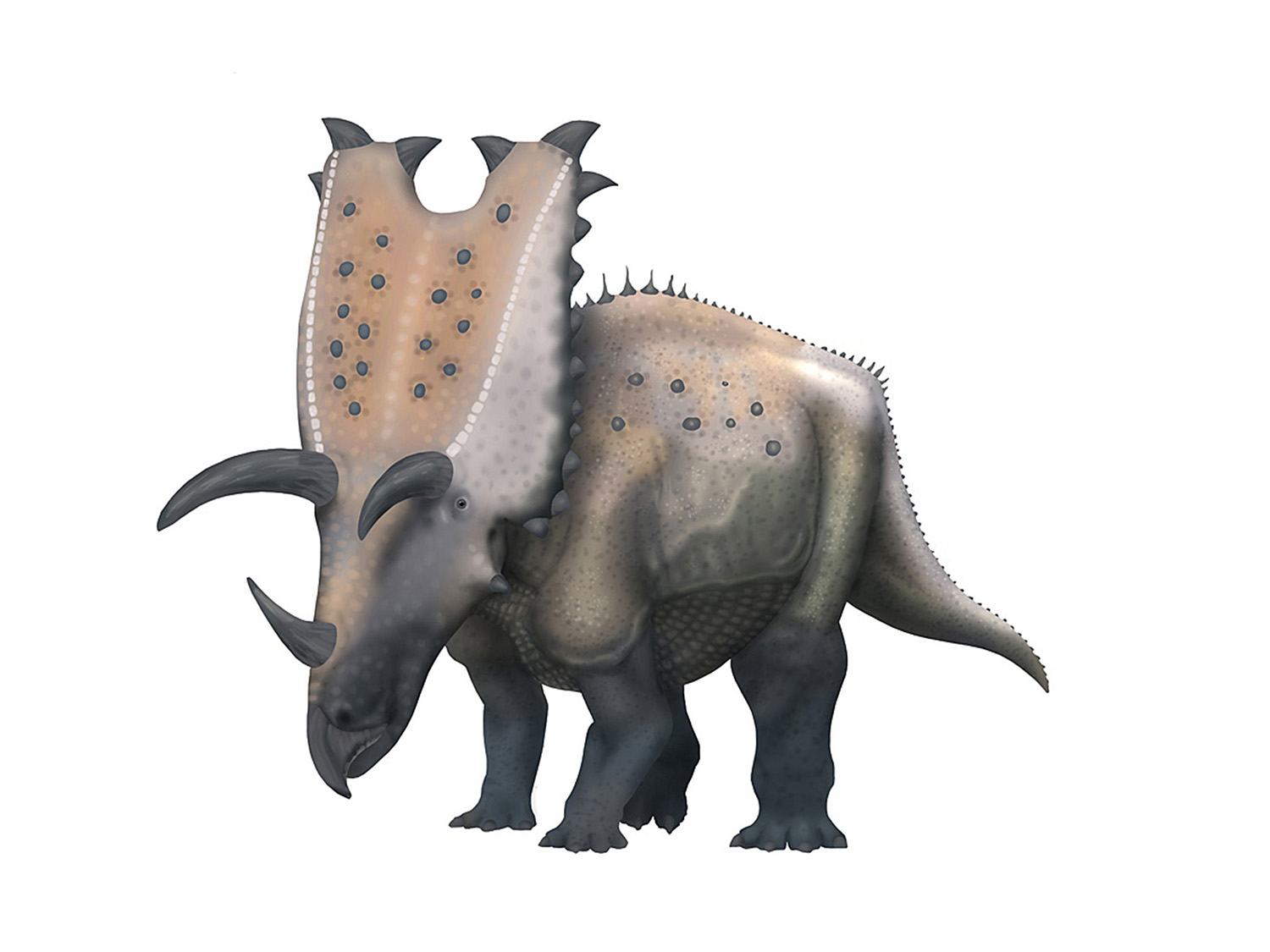

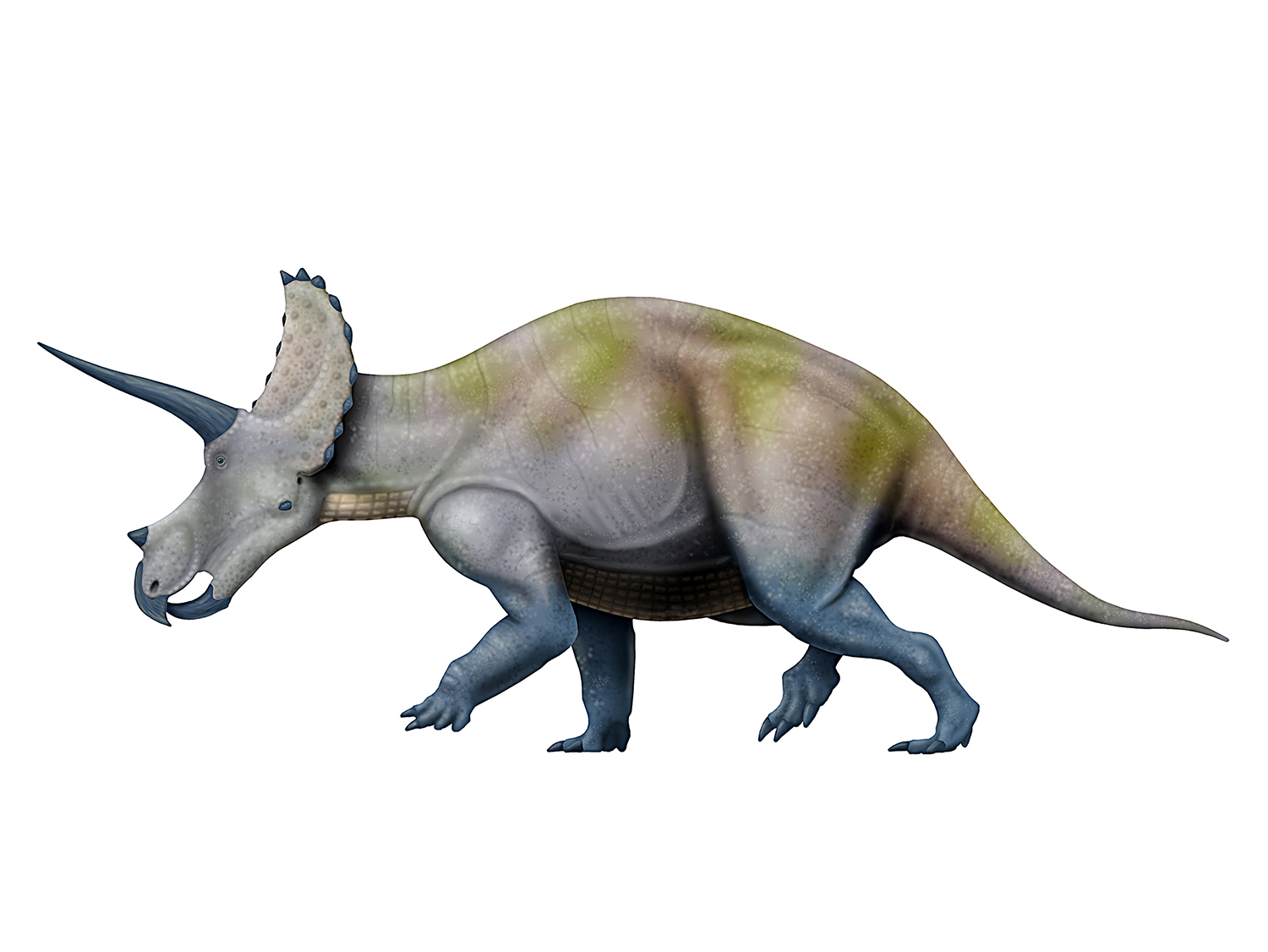

Much has been said about Bakker’s scientific role, but here we will concern ourselves with his contributions to the evolution of modern skeletal reconstructions. That story begins in his 1971 reply to critics in the journal Evolution, where he provides multi-view skeletal reconstructions of Struthiocephalus and Centrosaurus. Interestingly, they are comprised of solid black bones, with only a partial outline around the centrosaur. In some ways a style reminiscent of Scheele’s alternate skeletons in Prehistoric Animals (only without the eyeballs!).

(Image from Bakker's 1971 Evolution reply.)

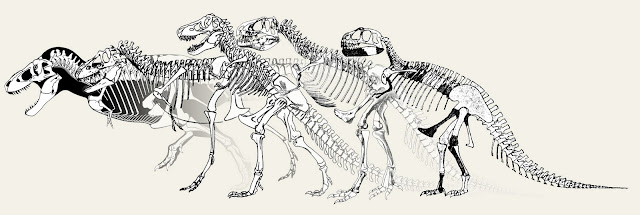

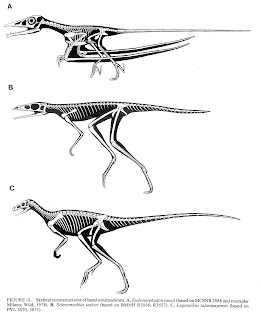

In 1974 Bakker and Galton wrote a paper with the modest goal of reuniting ornithischia and saurischia back into a single Dinosauria. Not only where they very successful, but in the process they provided a figure with not one, or even two, but three skeletal reconstructions with black profile silhouettes. The animals are all posed similarly for ease of comparison - pushing off on their left foot in a fast run. The pose isn't identical to the one eventually adopted by Greg Paul, but the influence seems clear.

(From Bakker & Galton's 1974 Nature paper.)

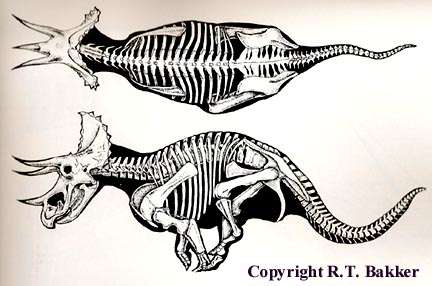

About this time a young Greg Paul had started to experiment with making skeletal and muscle reconstructions. In a trip to Robert Bakker’s lab in the late 1970’s he saw Bakker’s silhouetted multi-view skeletal reconstruction of a galloping Triceratops. Clearly it made an impression on him, and he started to put together skeletal reconstructions in a similar style soon thereafter.

(GallopingTriceratops, Copyright Robert Bakker, image from here.)

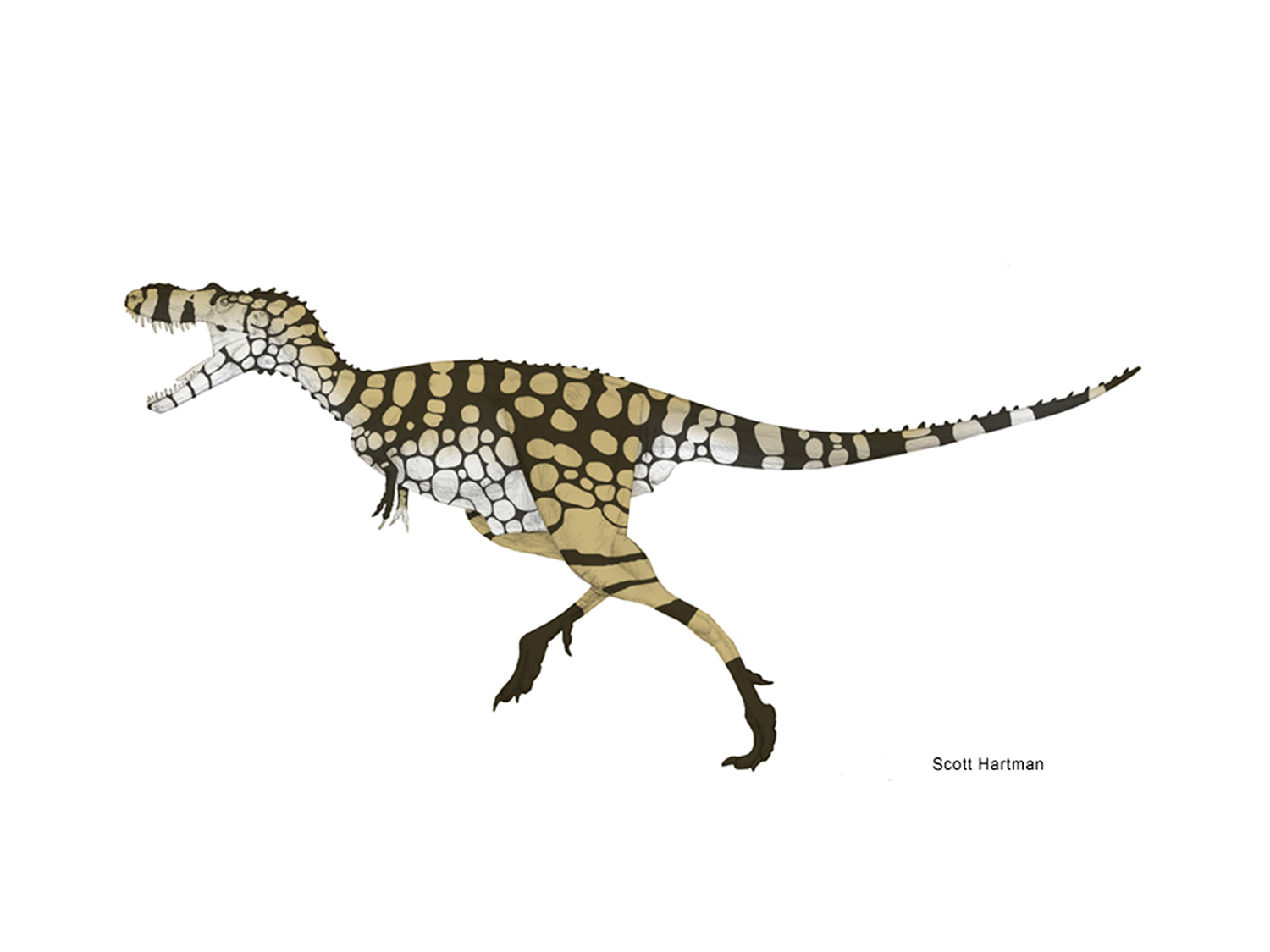

Bakker continued to produce skeletal reconstructions, including ones in the black-silhouetted mold. His 1986 book The Dinosaur Heresies is filled with different twists on this convention. One consistency Bakker has shown is a preference for stippling or line shading to convey depth to the bone structure, rather than the more minimalist white on black adopted by Greg Paul and others.

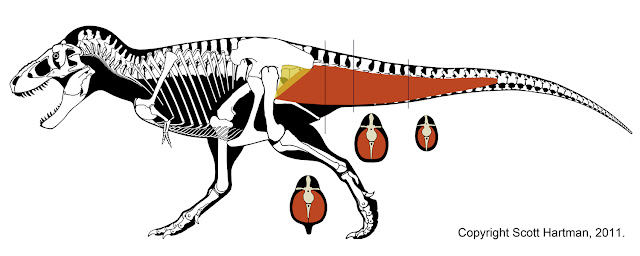

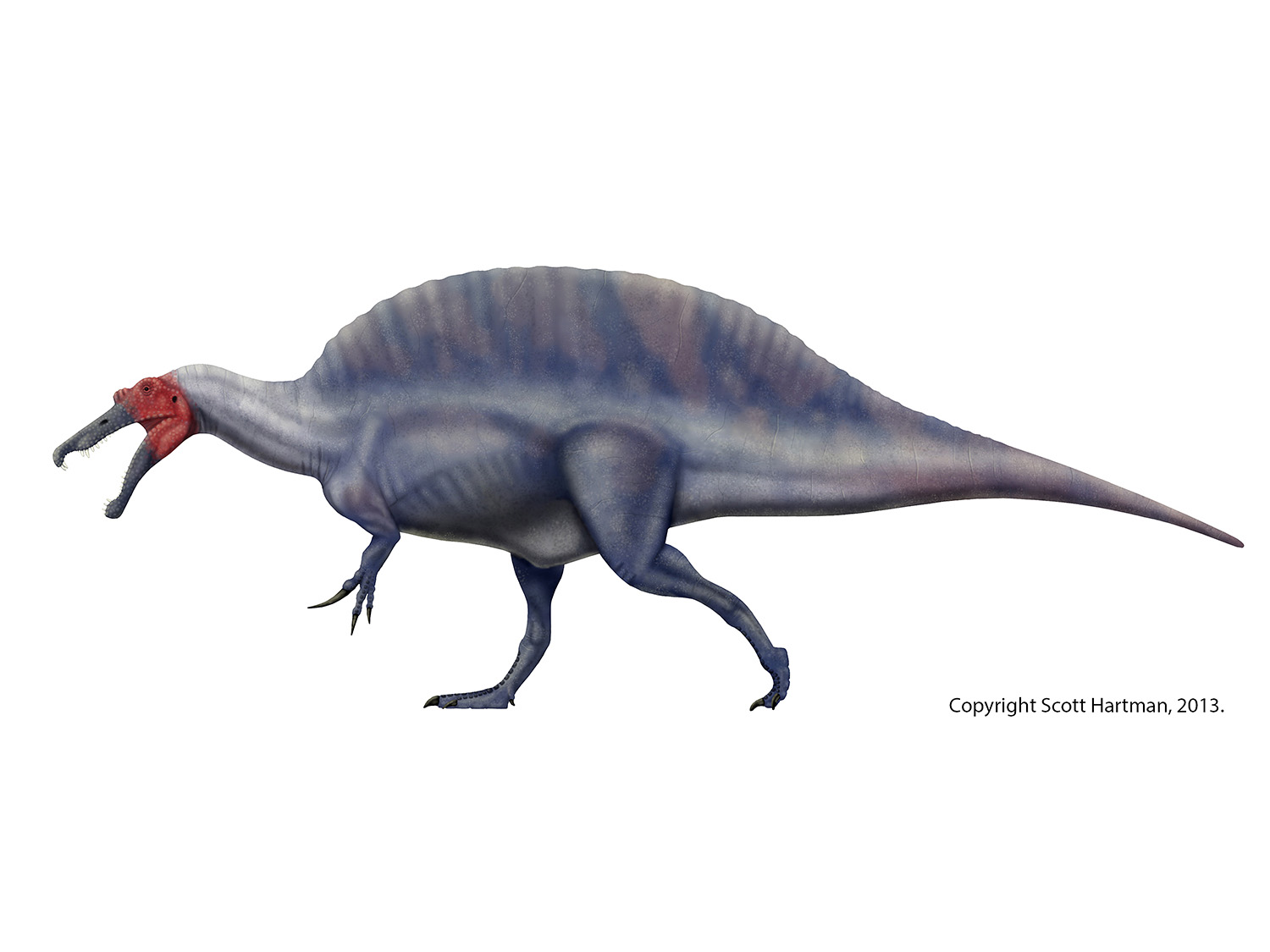

Bakker’s book did much to inspire another generation of dinosaur enthusiasts (not to mention researchers), but it was another book that really introduced the modern skeletal reconstruction a wider audience: Greg Paul's Predatory Dinosaurs of the World. For many of you I expect reading this part is sort of like watching Star Wars: The Phantom Menace since you already know how the story has to end. And 20 years later it's easy to be cynical about it. But the impact of that book on people interested in dinosaur anatomy, especially artists, is hard to overestimate; at the time no one had ever assembled such a large collection of modern skeletal reconstructions between the covers of a single book. It wasn't sheer quantity that impressed; the skeletal reconstructions were of closely related animals (theropods, it turns out) and were all in the same pose following the same set of anatomical assumptions. That made it possible to observe subtle differences in proportions, morphology, etc., without having your eye be mislead by inconsistencies of interpretation (shoulder blade placement, for example).

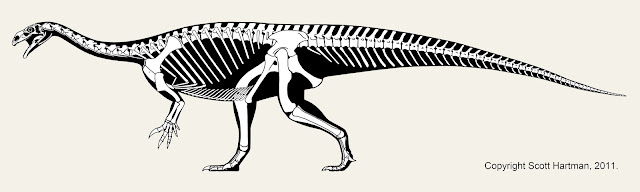

(Elaphrosaurus in PDW, copyright G.S. Paul.)

Professional reaction to the science in the book was mixed, but the long term impact on the field of skeletal reconstructions is incontrovertible. Combined with Paul's 1986 article on how to draw dinosaurs and his 1989 article explaining his technique for producing skeletal reconstructions, the popularization of the style would extend far and wide. Established researchers began to adopt the convention as well; just two years later in his 1990 memoir on basal archosaur relationships Paul Sereno adopted the black silhouette convention, as well as posing his skeletals consistently in a left-foot-pushing-off pose. His half dozen new dinosaur species described over the coming decade would all sport similar skeletal reconstructions.

Sankar Chatterjee, who had been producing line skeletal reconstructions for some time, also adopted the black silhouette convention (albeit with no consistent pose) in 1997 and has largely stuck to it as well.

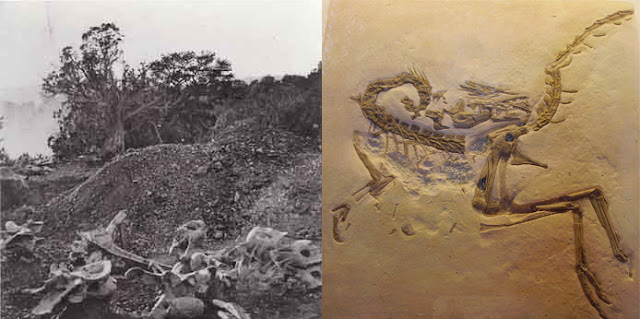

(Chatterjee's "optimistic" 1997 reconstruction of Protoavis)

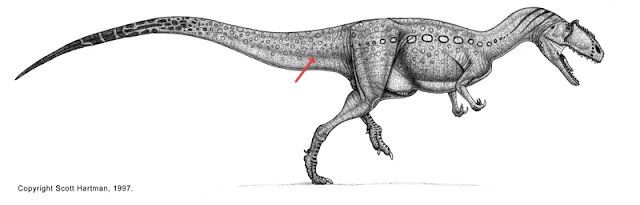

It was in this environment that I started attempting skeletal reconstructions. I started in the mid 1990s (there was a little known dinosaur movie that had helped to reignite my interest in dinosaurs), but it would take 4-5 years before I was producing skeletals I would view now as “professional”, and not until 2002 that I started to adopt a format that used the inset rigorous version. That format evolved from an idea that I picked up from Russell Hawley.

(This hack's artwork keeps popping up on my blog!)

Today of course the black silhouette is the norm rather than the exception. When new animals are described is has become de rigueur for a skeletal reconstruction to be published along side it, and more often than not it has a black silhouette around it. The primitive theropod Tawa is an excellent example of this. From established paleoartists like Mark Hallett, to more recent ones like John Conway, Jaimie Headden, and others too numerous to mention, it has become the standard way to represent skeletons. I should also note that many excellent artists around the globe have adopted this technique, with strong showings in South America and continental Europe in the last five years. Last year Greg Paul released a field guide of all of his dinosaur skeletals, making it feel like a true golden age for the study (and representation) of dinosaur anatomy.

Yet all is not well, and storm clouds have recently gathered on the horizon. Several weeks ago Greg Paul made a public statement that outlined stricter and less generous guidelines on who could use his work as a basis for life reconstructions (a refined official statement can be found on his website that I expect supersedes any other posts), and laid claim to the pose that his skeletal reconstructions popularized. Many of his complaints reflect a reasonable desire to not be ripped off by others who simply copy what he has done and call it their own. Some other requests are perhaps more dubious, but not being a copyright lawyer I will refrain from taking them up here. The take home message is that it is already impacting the field of skeletal reconstructions, and not always in good ways.

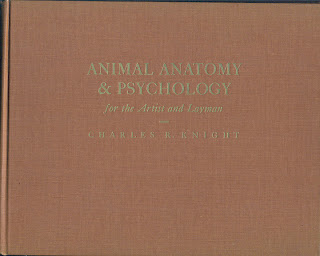

This concludes the history of skeletal drawings. For those who would have liked a more detailed look at the last decade, all I can say is we're still living that history, and I'm somewhat gun-shy about making claims about how influential a given event or artist when so little time has passed. I doubt many realized the importance of Knights book on animal illustration for paleontology, nor did many recognize Walker's work on Stagonolepis as anything more than an excellent monograph. It's after the fact that it becomes clear where the inflection points are in history. So hurry up and do your best work, so that future generations of bloggers may include our names in a favorable light.

Instead it's time to look to the future, post Paulageddon. It's time to take a hard look at what it means for skeletals, and what we can do as a community to produce some good from all of this. I will probably have a couple of anatomy posts in the interim, as they are quicker to produce (and let's face it, what the blog is really about), but fear not; skeletal reconstructions and the issues that surround them will be on a reoccurring theme here at SD Blog.

Happy paleoarting!

References

Bakker, R.T. (1971) Dinosaur bioenergetics - A reply to Bennett and Dalzell, and Feduccia, Evolution. v28, n3, pp 497-503.

Bakker R.T. & Galton, P.M. (1974) Dinosaur monophyly and a new class of vertebrates, Nature v248, pp 168-172.

Currey, J.D. (1962) The histology of the bone of a prosauropod dinosaur. Palaeontology. v5, n2, pp 238-246.

Ewer, R.F. (1965). Anatomy of the thecodont reptile Euparkeria capensis Broom, Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences. v248, n751, pp 379-435.

Galton, P.M. (1970) The posture of hadrosaurian dinosaurs, Journal of Paleontology. v44, n3, pp 464-473.

Ostrom, J. (1969) Terrestrial vertebrates as indicators of Mesozoic climates. Proceedings of the North American paleontological convention, Field Museum of Natural History.

Paul, G.S. (1986). The Science and Art of Restoring the Life Appearance of Dinosaurs and Their Relatives: A Rigorous How-To Guide. Dinosaurs Past and Present Volume II (eds. Czerkas, Olson), Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County Press.

Paul, G.S. (1988). Predatory Dinosaurs of the World: A Complete Illustrated Guide. Simon & Schuster, pp 464.

Paul, G.S. & Chase, T.L. (1989). Reconstructing extinct vertebrates. In The Guild Handbook of Scientific Illustration, Van Nostrand Reinhold, pp 239-256.

Russell, L.S. (1965) Body Temperatures of Dinosaurs and its relationships to their extinction. Journal of Paleontology, v39, n3, pp 497-501.

Walker, A.D. (1961). Reptiles of the Elgin area: Stagonolepis, Dasygnathus and their allies, Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences. v244, n709, pp 323-373.

Walker, A.D. (1970) A revision of the Jurassic reptile Hallopus victor (Marsh), with remarks on the classification of crocodiles. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences. V. 257, N. 816, pp 103-204.

Wieland, G.R. (1942) Too hot for the dinosaur! Science, New Series, V.96 N.2494, pp359.

Young, C. (1960) The pseudosuchians in China, Palaeontologica Sinica. New Series C, N. 19.