Skeletal Poses: Do they matter?

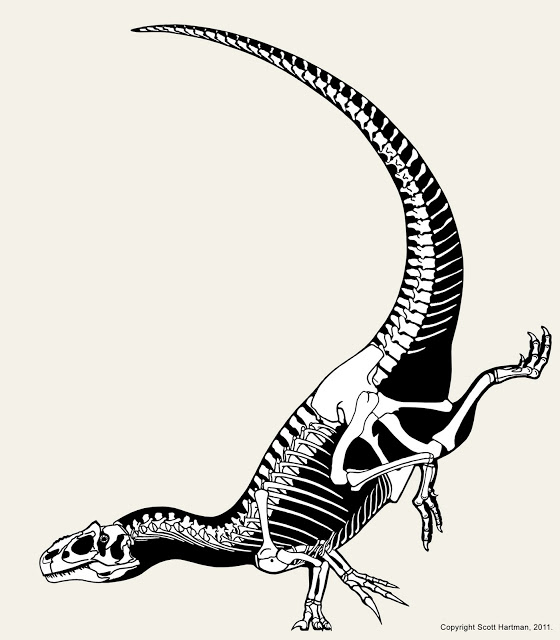

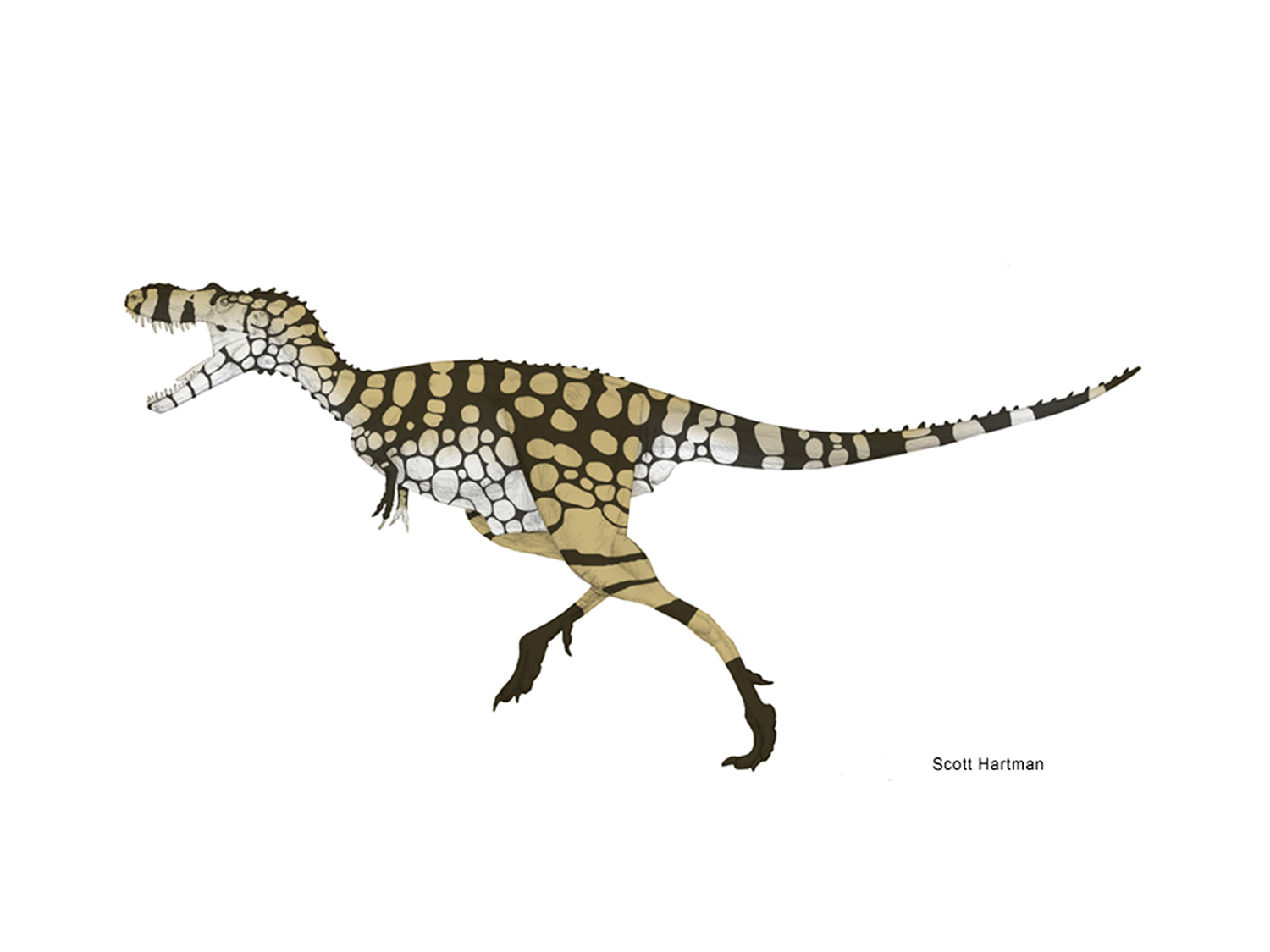

/Ok, first stop chortling. Then take a good look at the handstand allosaur up there. In several respects it's scientifically accurate - the bone outlines reflect the actual morphology of the fossils, and the proportions are correct, so it's a "realistic" skeletal reconstruction. The pose is certainly unusual, but none of the joints are disarticulated. In these respects it's better than many of the skeletals that appear in peer-reviewed journals. Yet I think it's safe to say that most researchers would consider that allosaur to be in a biologically implausible position.

Do skeletal poses matter?

Is this pose just as good as any other, or are in fact some choices more useful? After the break I'll try to make the case that choosing a pose is an important part of making a skeletal reconstruction, rather than a random after-thought.

I shouldn't have to say this, but just to be clear: I don't think Allosaurus could do a handstand. Even attempting it would probably lead to a dramatic reduction in life expectancy. Yet if all a skeletal reconstruction is supposed to do is to show off the bones, then the only real complaint in the image above is that the left leg obscures the pelvis more than necessary.

So why not use this pose? Certainly it would be easy to build up a "brand" around such a pose. Yet I'd submit to you that skeletal reconstructions with inaccurate biomechanics undercut the value of a skeletal by virtue of the added theoretical "baggage". Mike Habib, clever gentleman that he is, anticipated this point in his comment on the previous article, which I'll quote below:

"...it is distracting from the point of the reconstruction if the viewer spends time trying to work out if the pose is realistic. Ideally, a "standard" pose should be a 'no-brainer' for most taxa, so that viewers can focus on, you know, the *skeleton*."

In addition to distraction, poses that are not feasible (or even just unlikely) create other problems; some authors will avoid such skeletals (perhaps even choosing a reconstruction that is otherwise less accurate). There will inevitably be well-intentioned artists that introduce incorrect poses into their work. And of course other scientific illustrators may be scared off of using the same pose, making comparisons between bodies of work more difficult.

If we only dealt with ludicrous poses, this may seem like a straw man argument. So let's consider a less overt example:

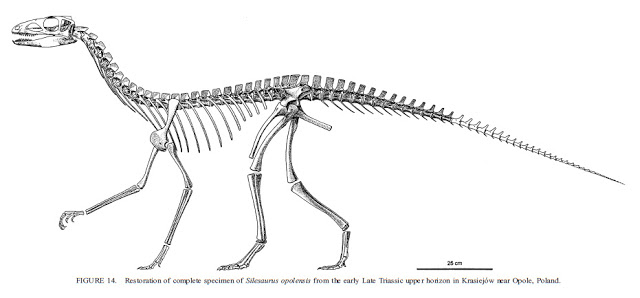

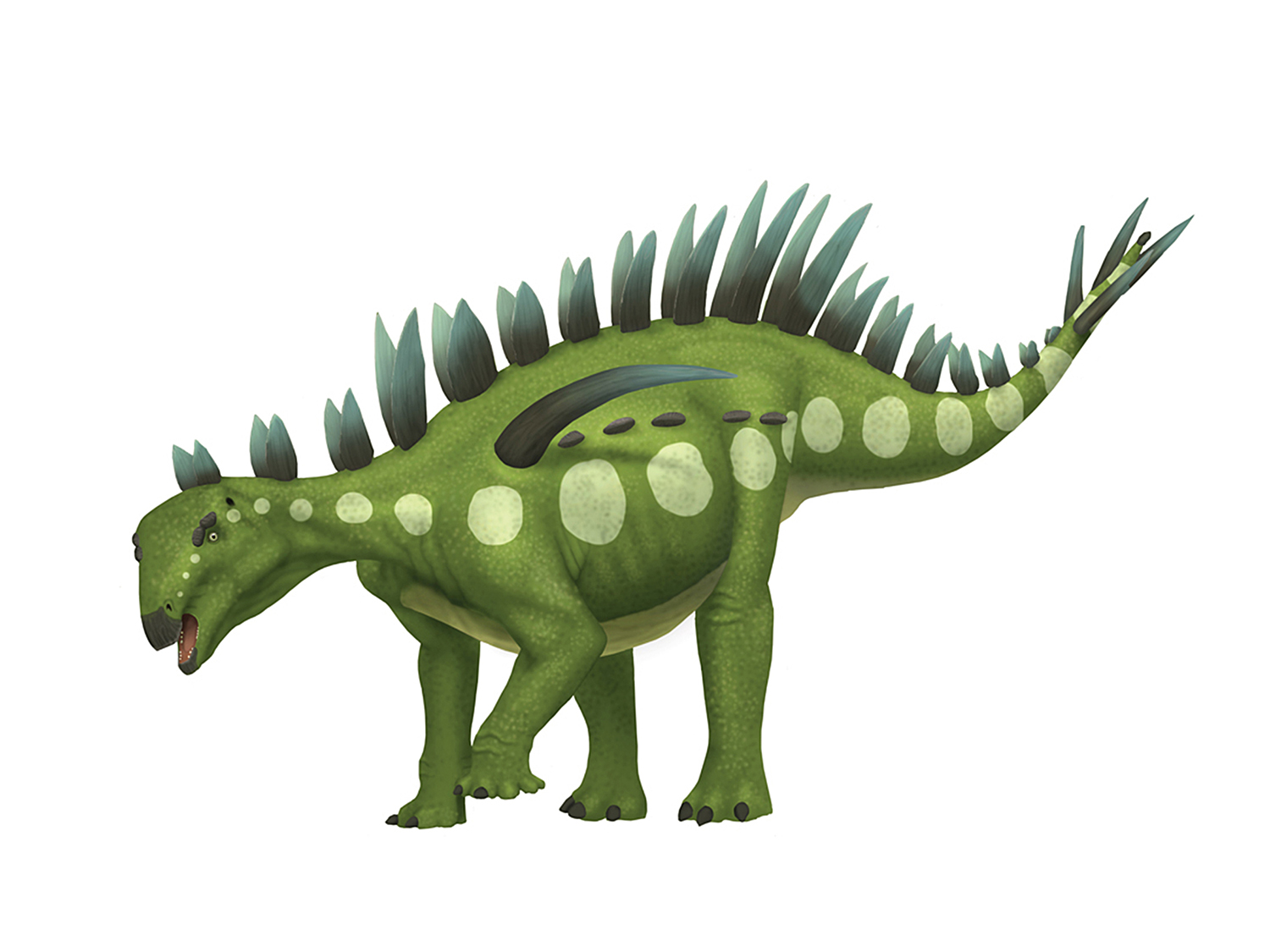

That's Silesaurus, from the original description in JVP. The shapes of the bones generally reflect the individual elements described in the manuscript, and the proportions are quite good; clearly it's intended as a realistic skeletal reconstruction. The pose is certainly not wrong in some over-the-top manner, yet there are several problems with it. Some differences are due to different interpretations of rib orientation and pectoral girdle positioning (but that's another post...), while others are not so easily categorized.

The vertebral column in general is problematic; the flex in the base of the neck and the overly-straight back are positions that may be possible, but would not be terribly common for the animal. The forearms are pronated to a degree that is unlikely in such a primitive dinosauromorph. Even more clear-cut is the position of the right forelimb. The right humerus (the upper arm bone) is so far forward it would be completely dislocated from the shoulder socket. Moreover, given the position of the visible part of the humerus the proximal part would be articulating with the center of the coracoid, rather than the glenoid fossa (the shoulder joint).

If the only thing you care about is the bones, then I admit that how distracting these issues are depends on how closely you pay attention to biomechanics. But the pose isn't without repercussions; a quick image search shows that several derivative skeletal drawings have been produced that perpetuate the same errors, and a decent number of life reconstructions also exhibit those errors.

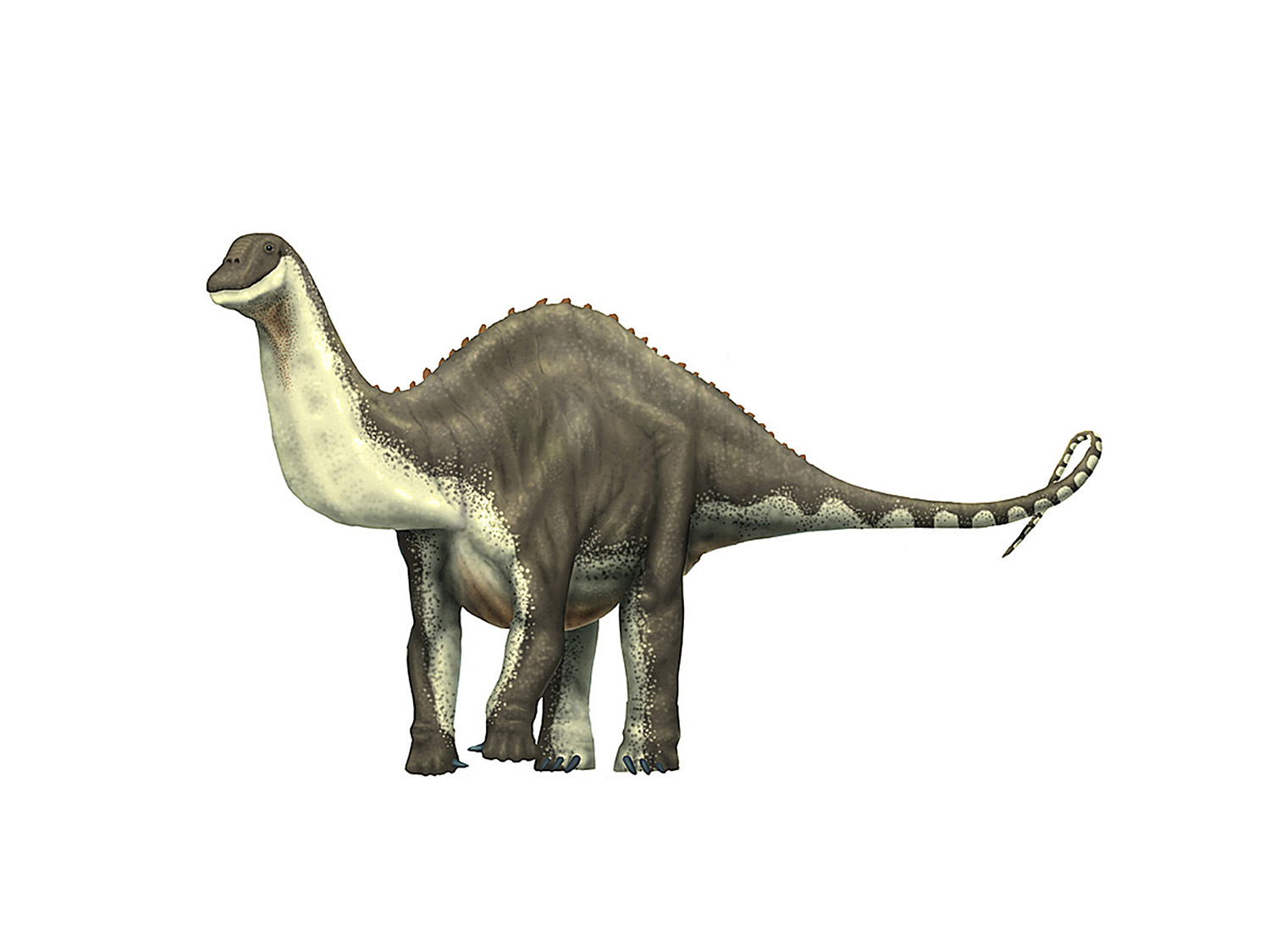

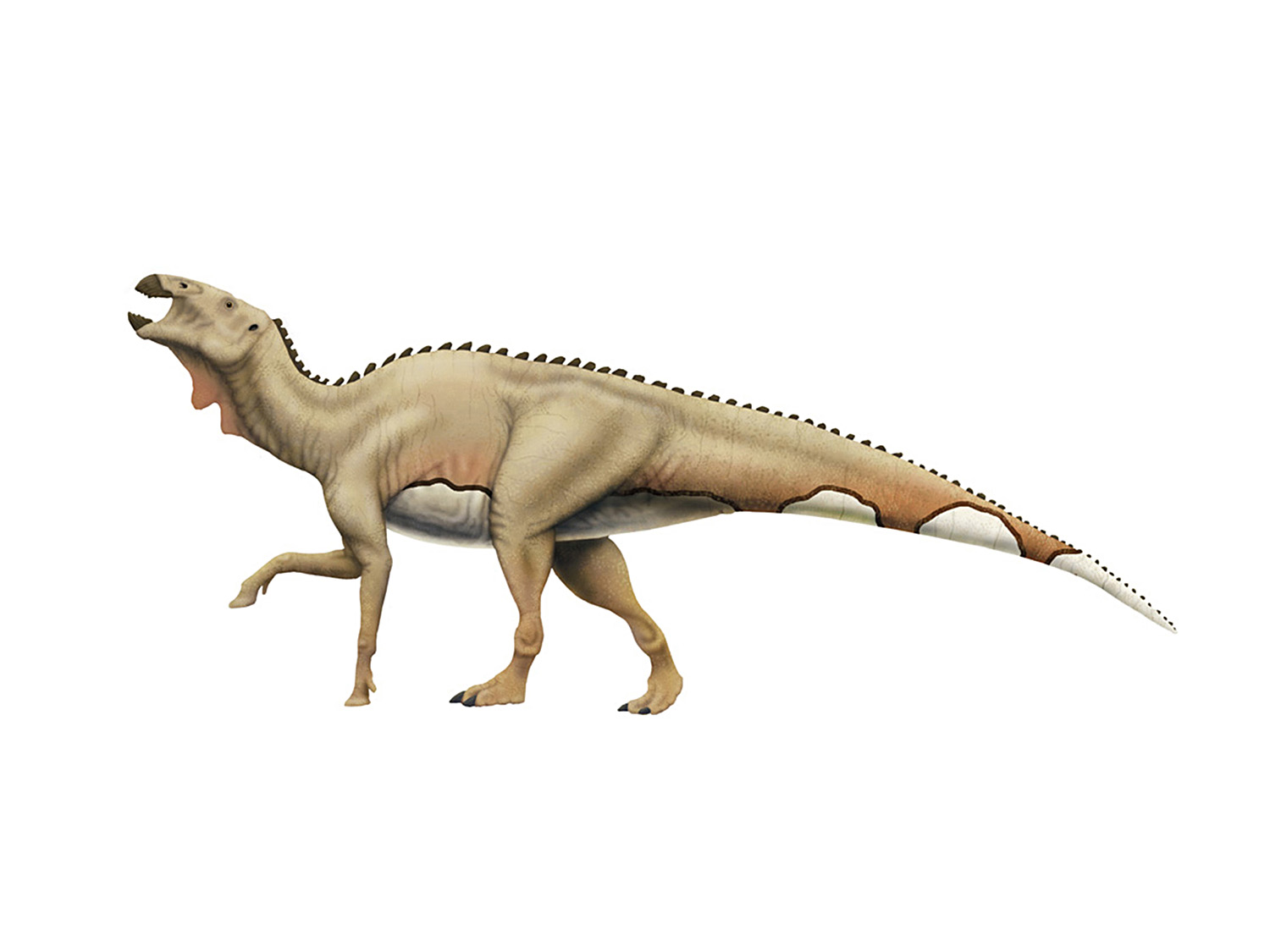

(Image from here; artist unattributed.)

To some degree this is where we get to the crux of disagreements - people are often quick to criticize as outlandish the problems that appear at the macroscopic level (Allosaurus can't do a handstand!) while ignoring the problems that are less obvious, or at least the ones that fall out of their area of expertise. As a result I'd be willing to bet cold hard cash that the handstand allosaur at the top would not make it past the same reviewers that gave a pass to the Silesaurus paper, even though the skeletal in that paper is a less biologically plausible pose than the allosaur.

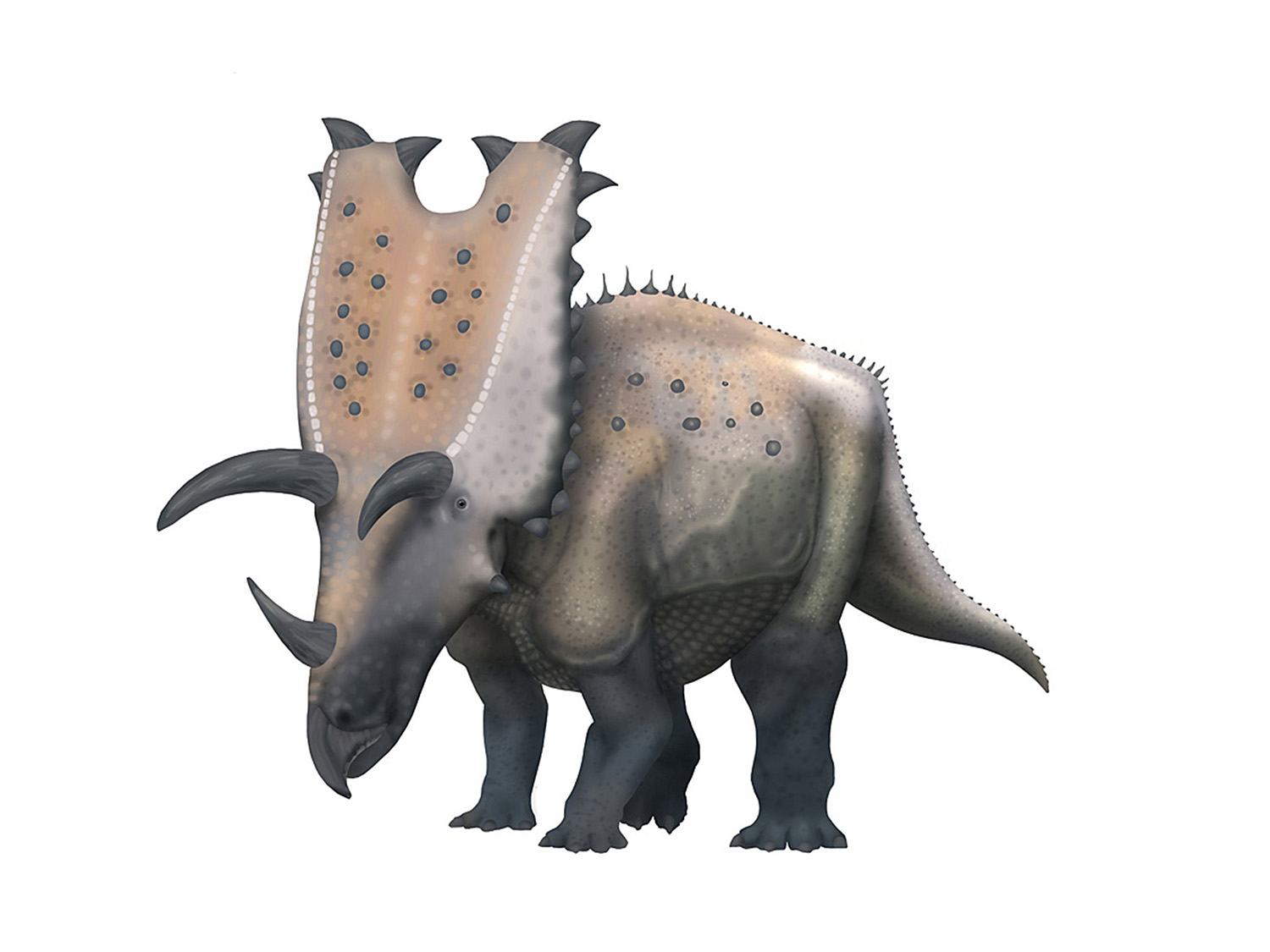

If people really want to present just the bones, and not make any statement about functional anatomy at all, perhaps researchers should consider exploded diagrams:

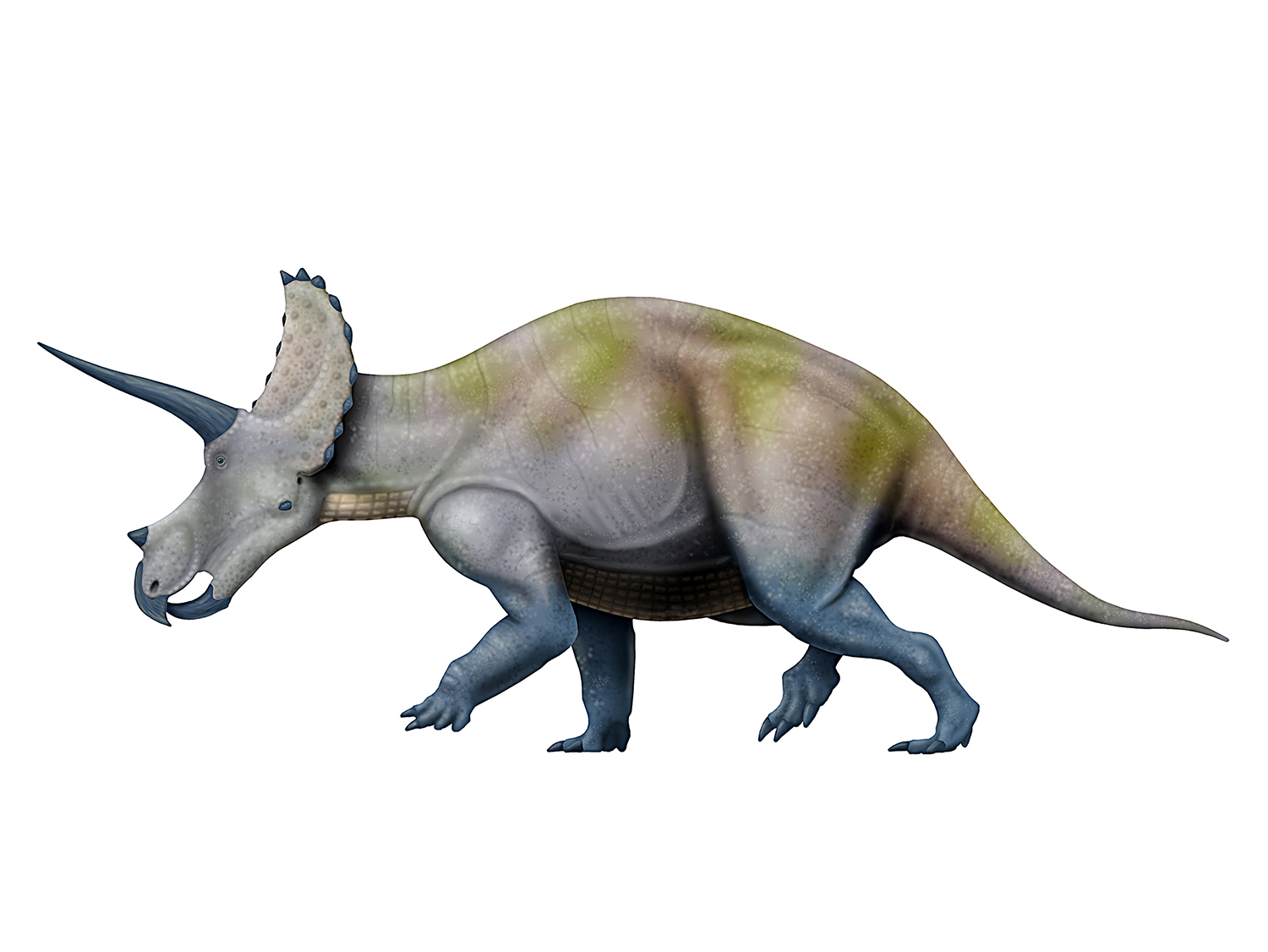

Exploded diagrams have a proud tradition in technical illustration, and can be done without making any statement what so ever on functional morphology. I should note that the above diagram is a butchered version of my Styracosaurus skeletal; in a diagram prepared from the start to be an exploded diagram I would expect the limb bones and possibly even the vertebrae to not be connected as in life. Providing all of the bones scaled (and revealing only the preserved portions) would accomplish the purely descriptive goals of a traditional skeletal (perhaps even be superior, since nothing is hidden by the limbs) and completely relieves authors/illustrators from making explicit claims about how the animal went together.

So in conclusion, the point I want to make is this:

People do not have to put realistic skeletal poses in their papers. They can use schematic diagrams (which partially relieves the burden) or use exploded diagrams (which completely removes it). The exploded diagram in particular conveys more morphological evidence then a traditional skeletal drawing, while being 100% agnostic about biomechanics.

If authors/illustrators do choose to do a realistic skeletal reconstruction, then they should accept the need to place them in biomechanically sound poses. Inaccurate poses can distract from the other purposes of a skeletal diagram, and may mislead paleoartists. Down the line if such diagrams get incorporated into educational diagrams they also play a role in confusing students and consumers of popular scientific media...but that, two, is another post.

In the mean time, remember: Poses are important!