The lines that divide us

/No, this isn’t about the ethics of skeletal reconstructions. Instead it’s a look at the hazards of drawing lines in scientific illustration, and something of a justification for the silhouette-bound skeletal drawing. There are some snippets on how to make better skeletal drawings yourself if that’s your thing. And perhaps of greater interest to many readers, it’s background for a major change coming soon to a large chunk of my skeletal drawings.

But first, I have a challenge for you, should you choose to accept it: Look at the image of the femur with scale bar and provide an estimate of its length. Maybe share it in the comments below? Feel free to download it and print it out, or pop it into Photoshop or ImageJ to use the measure tools if you’re so inclined. Or just hold out your thumb and do your best. You can do it right now if you want, I can wait…

…back? Good! This is a fairly typical situation you might find yourself in when reading a descriptive paper that uses illustrations instead of photos (photos have their own challenges). Presumably those of you who tried to eyeball it there would report a fairly wide range of lengths - no real surprise, as spatial powers of estimation vary quite a lot from person to person, plus a lot of minor things could introduce error to the process (e.g. shifting your laptop around as you try to guestimate it). That is, of course, why in science we try to find more precise ways to measure things and to share those measurements. For those of you wwho printed it out, or used software, presumably there would be a narrower range of results, but you still might run into problems with the resolution of the image, picking slightly different “longest” points to measure from, etc.

But here’s the rub: Even if a lot of you used a ruler (or a digital measuring tool) and I had supplied an enormously high resolution image that would have cripple mobile data contracts, I would expect at least a 5% difference the the answers found.

Why? Because the difference between measuring the femur from outside edge of the line to outside edge on the other end, vs measuring from the inside of that line on one side to the inside of the line on the other is 3% by itself. And a similar problem crops up when you try to measure the scale bar - should you measure it from the outside of the lines, the inside of the lines, or somewhere right in the middle of the lines?

In my experience most people pick a point somewhere within the line (which is only 2-3 pixels at this resolution, but could be a lot more at higher resolutions) and assume it’s measured “correctly”, but unless a caption explicitly says how to measure a line drawing (and I don’t believe I’ve ever seen a caption say that) the very fact that a line is used that is multiple pixels thick introduces a source of error automatically.

You might think that 5-6% isn’t so bad - and depending on what you are using it for, maybe it isn’t too terrible. But I think that most people (and certainly most scientists) would be less-than-thrilled with the idea that the act of sharing their measurements automatically makes them 5%+ off even before more run of the mill human error is taken into account. Of course you can get around that by publishing measurements rather than relying on scale bars (a subject the good folks over at SVPOW have already discussed in detail). But this is a blog about skeletal drawings, so I want to bring it back to this:

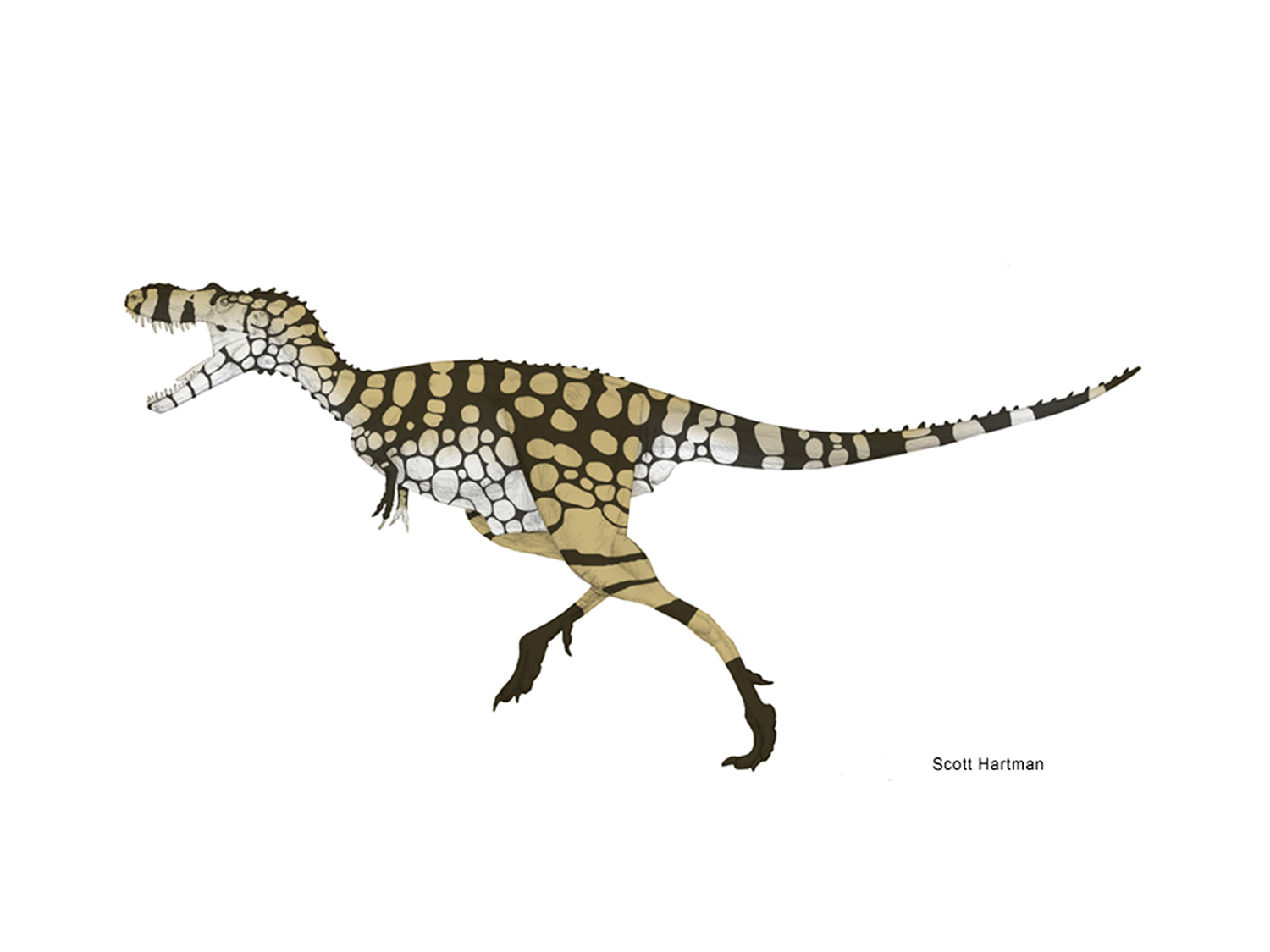

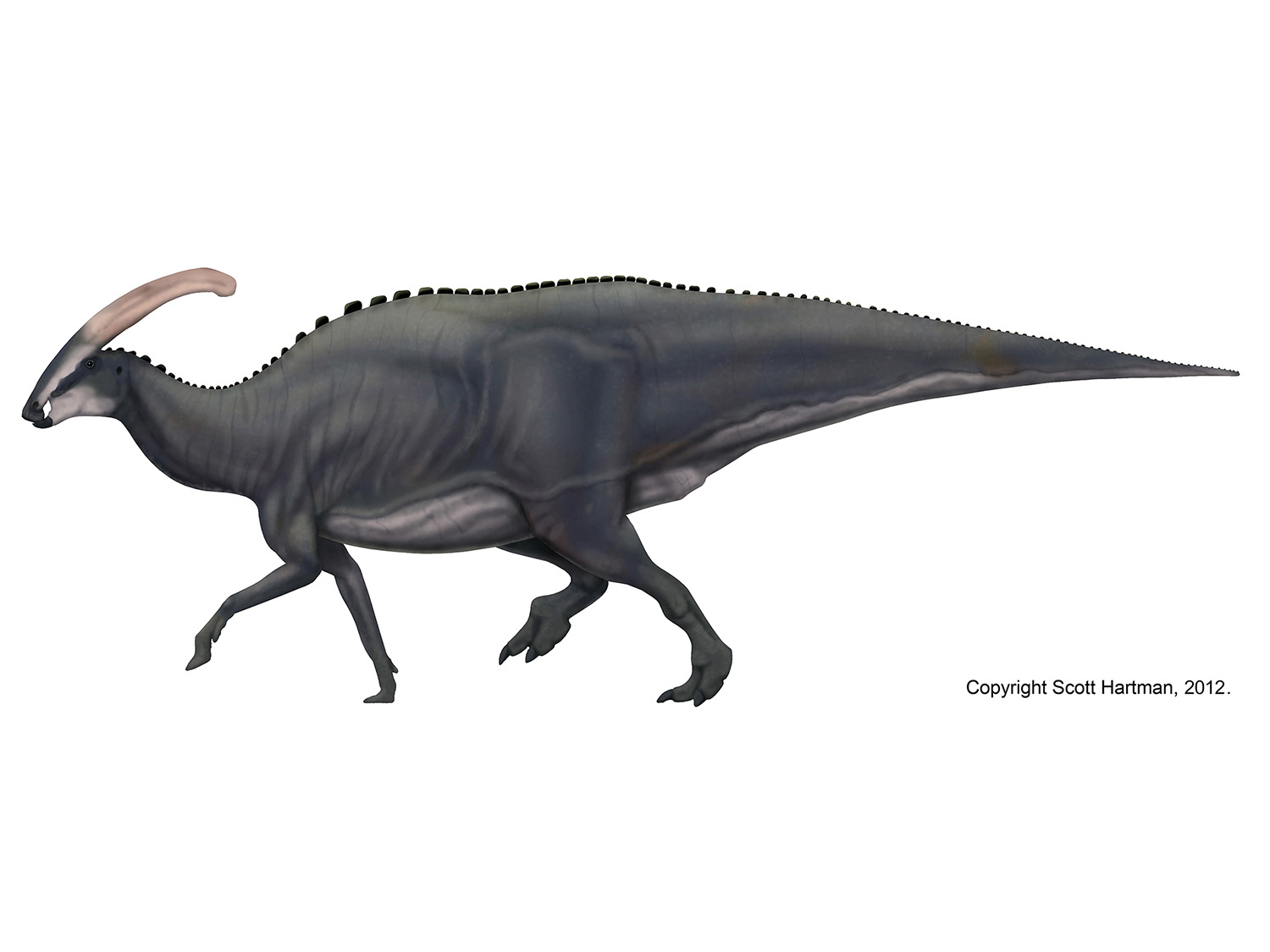

If we reran the experiment with this femur (which, to be sure, is the same femur just surrounded by a silhouette) there should be a smaller range of reported values (discarding errors in scaling. That’s because there is less ambiguity about where to measure from - for both the femur and the scale bar it’s the transition between solid black and solid white pixels. The low resolution of these images means there/s a bit of anti-aliasing that makes this transition take up a pixel or more, but with the resolution you’d find in print or a decent pdf that wouldn’t exist, which immediately clears up the 5%+ error that stemmed from using outlines. I would argue that is the primary advantage of skeletal drawings. Even Greg Paul in his seminal 1988 book Predatory Dinosaurs of the World wrote about this, saying:

“Profiling bones in black has the advantage of being truer to their shape than outlining. This is true because the edge of an inked area marks the exact boundary of a bone, as opposed to a single ink line which straddles the bone’s boundary and makes it appear slightly larger than it actually is.”

There are plenty of things I could take issue with in PDW, but this isn’t one of them. Of course this only works if you draw the bones with this in mind - you need to outline around the shape of each bone; if you follow the more intuitive practice of drawing a line that straddles the bone boundary and then surround the bones in a silhouette the bones will all appear too small in the final skeletal reconstruction. In fact I’m pretty sure I’ve seen this effect in several skeletal reconstructions on the web (I’m not judging - I did this too on my early attempts…but luckily for me that was back in the 1990s and not everything was posted to the internet).

What this means for skeletal reconstructions:

First off, if you want to measure bones in my skeletal reconstructions using the scale bar be sure to only measure the white portion of a bone - even when the bone in question (e.g. a femur) has to have a line where it overlaps another bone (e.g. an ilium) the line itself is not part of the bone, only the white portion is.

Second, if you’re going to do skeletal drawings in a silhouette, you should probably be sure that you are drawing individual bones correctly. It’s not terribly intuitive at first to draw a bone this way (by default we draw lines that are centered on the boundary of an object) but with a little practice it can become almost second nature, and failing to do so will result in the bones all looking undersized.

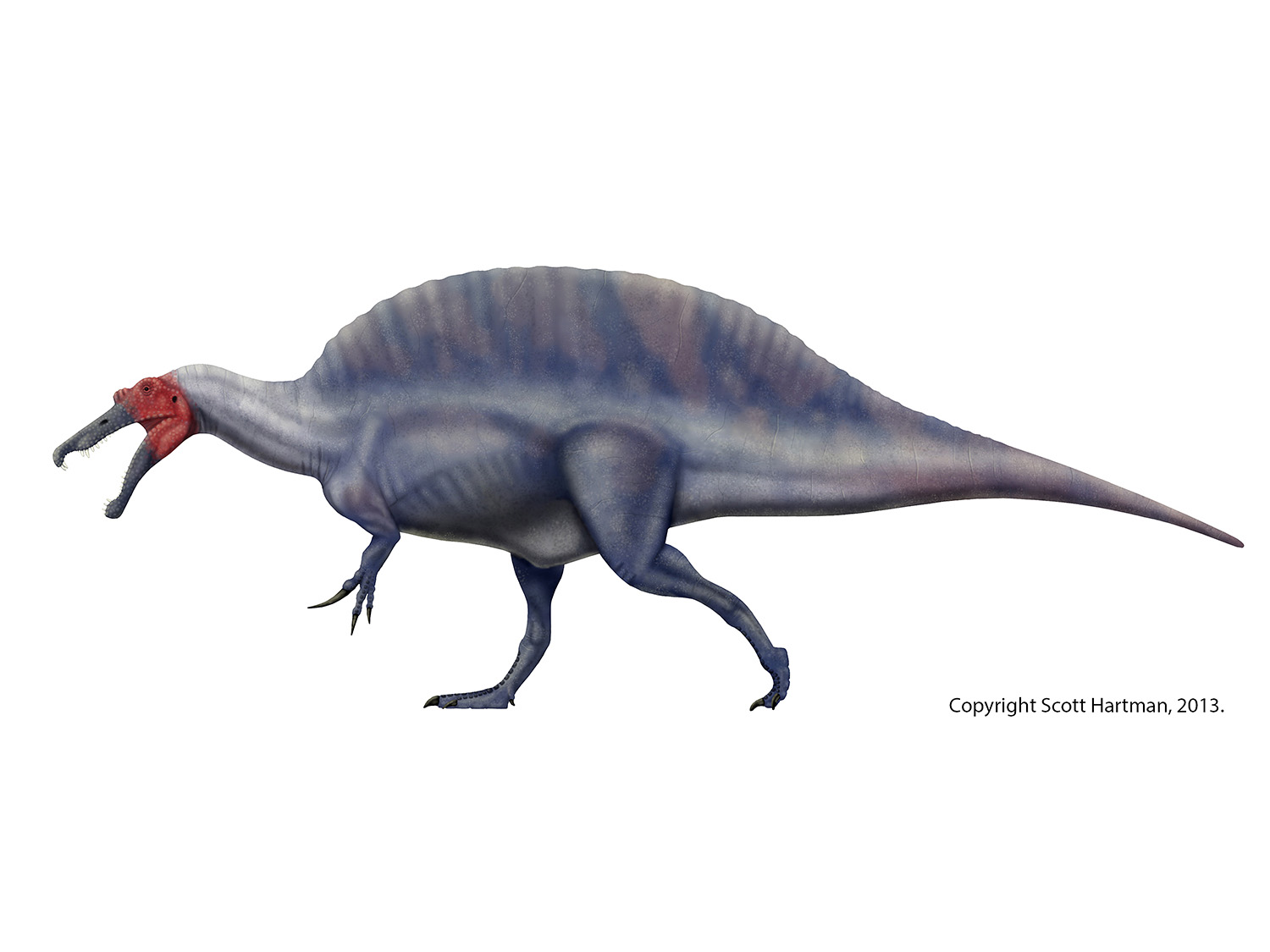

Finally, I have often been asked why I don’t draw the teeth of some of my dinosaurs, e.g. theropods, in white. After all, it would show them off better (not half-buried in the soft-tissue line, or gums, or small lips), and everyone loves to see the big, scary teeth of theropods, amirite?? The reason I had always avoided this (unless necessary for a commissioned project…the customer is always right!) is because the fact that teeth may stick out beyond other soft-tissues forces the illustrator to pick between two bad choices:

1) If you draw the bone on the outside of each tooth (as you should for bones within the silhouette) then it because the line is stick out beyond the rest of the silhouette is makes the teeth look bigger (sometimes much bigger) than they should in real life. That might appeal to fans who want their theropods a bit more awesomebro, but it’s misleading for everyone else - and the larger size would almost certainly get perpetuated in future paleoart based on the skeletal.

2) If you don’t draw the line outside the teeth, then you preserve the correct size of them in profile view, but you are actively misleading viewers about how to interpret the rest of the skeleton.

So basically either way it going to require a lack of consistency, which is why I’ve avoided it. But I can’t any longer…more on that very soon.