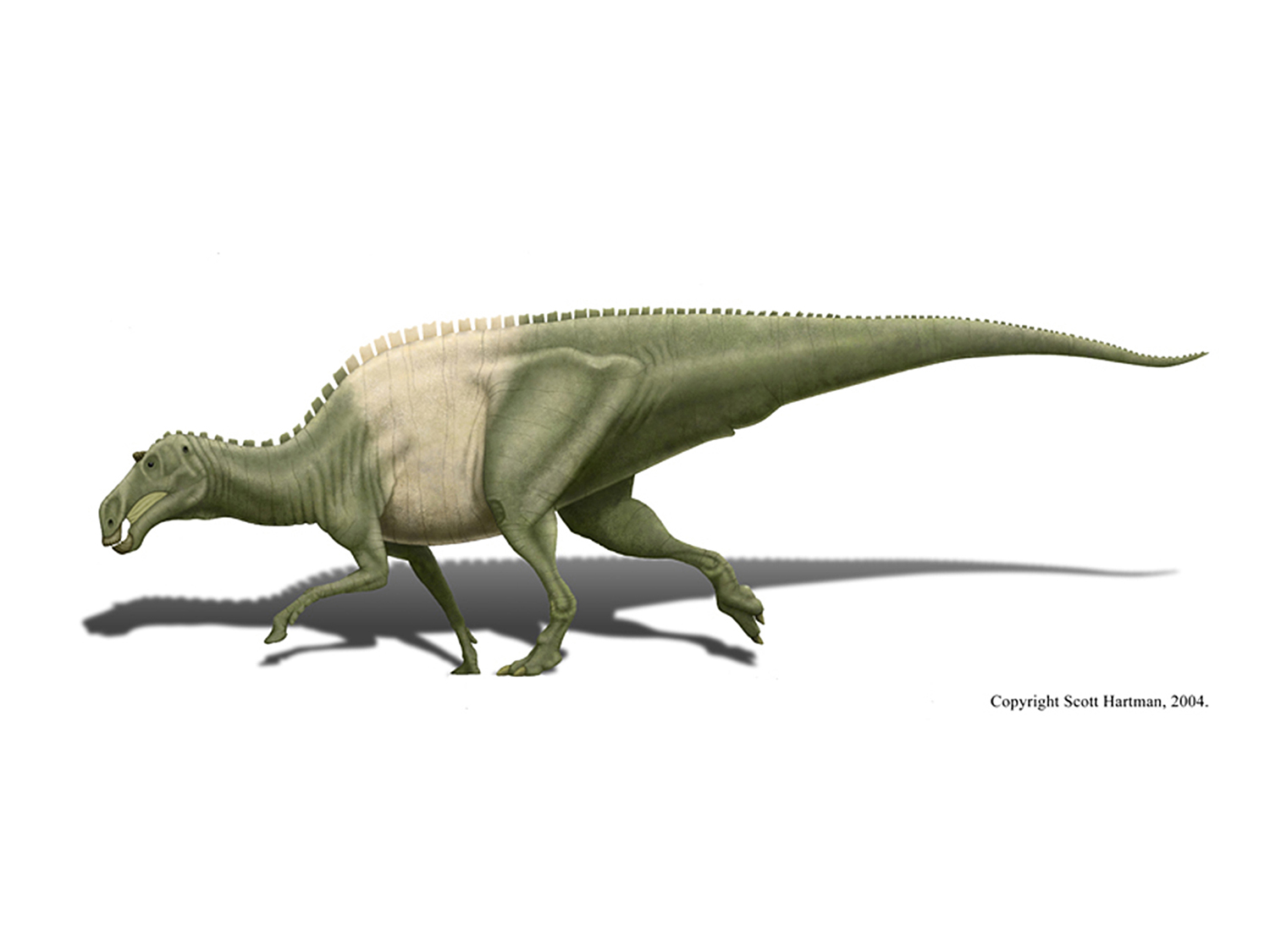

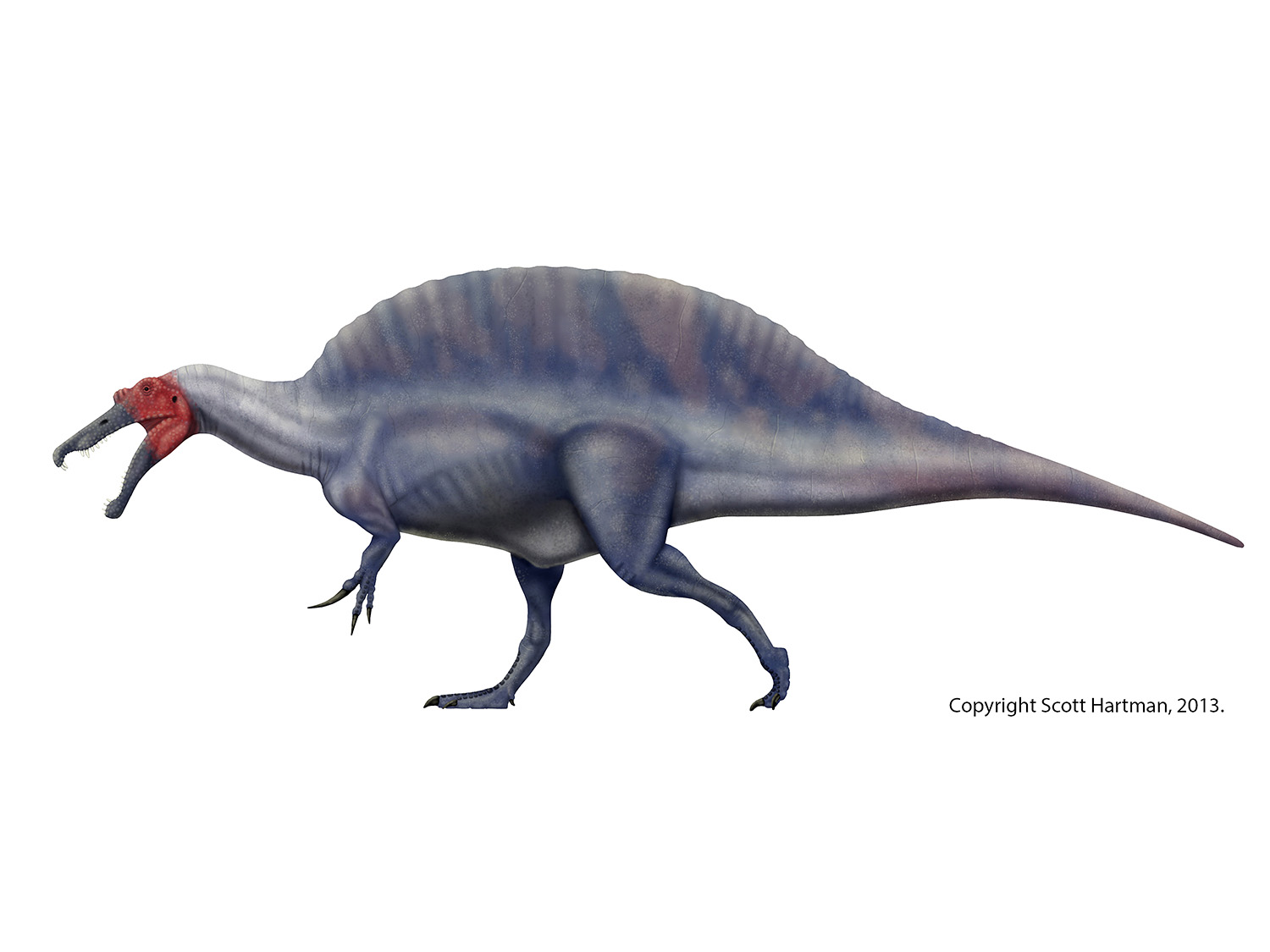

WithSpinosaurus temporarily out of the way, we're going to take a closer look at Acrocanthosaurus. This series is going to include a post on what we know and don't know about Acrocanthosaurus, how to restore the skeletal in multiple views, and how to restore the muscles. At the end of that series I'll also comment on some areas of soft-tissue variation that artists should keep in mind when they envision "their" Acrocanthosaurus.

First though, I wanted to take a moment to look at how my own reconstruction of Acrocanthosaurus has changed over the last decade. With any luck some of my earlier errors in methodology might help others who want to do skeletals. Also I hope to provide some insight to how I update skeletals over time, and the importance of revising your work as new data is published.

Although Acrocanthosaurus is hardly the best known theropod, it provides more than its share of challenges when attempting to reconstruct it. In my case, I attempted the original skeletals during what I'd call a methodological nexus - it was one of the first skeletals I attempted within an entirely digital environment, and to some degree the initial reconstruction suffered as a result. I had developed many techniques when I executed skeletals in pen and ink, and most of those translated fairly well during the years (roughly 2000-2004) when I used a hybrid method of digital and ink work. Alas, attempting to work entirely inside a computer forced me to rediscover how to accomplish the same things inside of Photoshop, and as a result the first couple of attempts were actually a step backward in some ways. Luckily I stuck with it, and the results are now far better then anything I accomplished in the "analog" world.

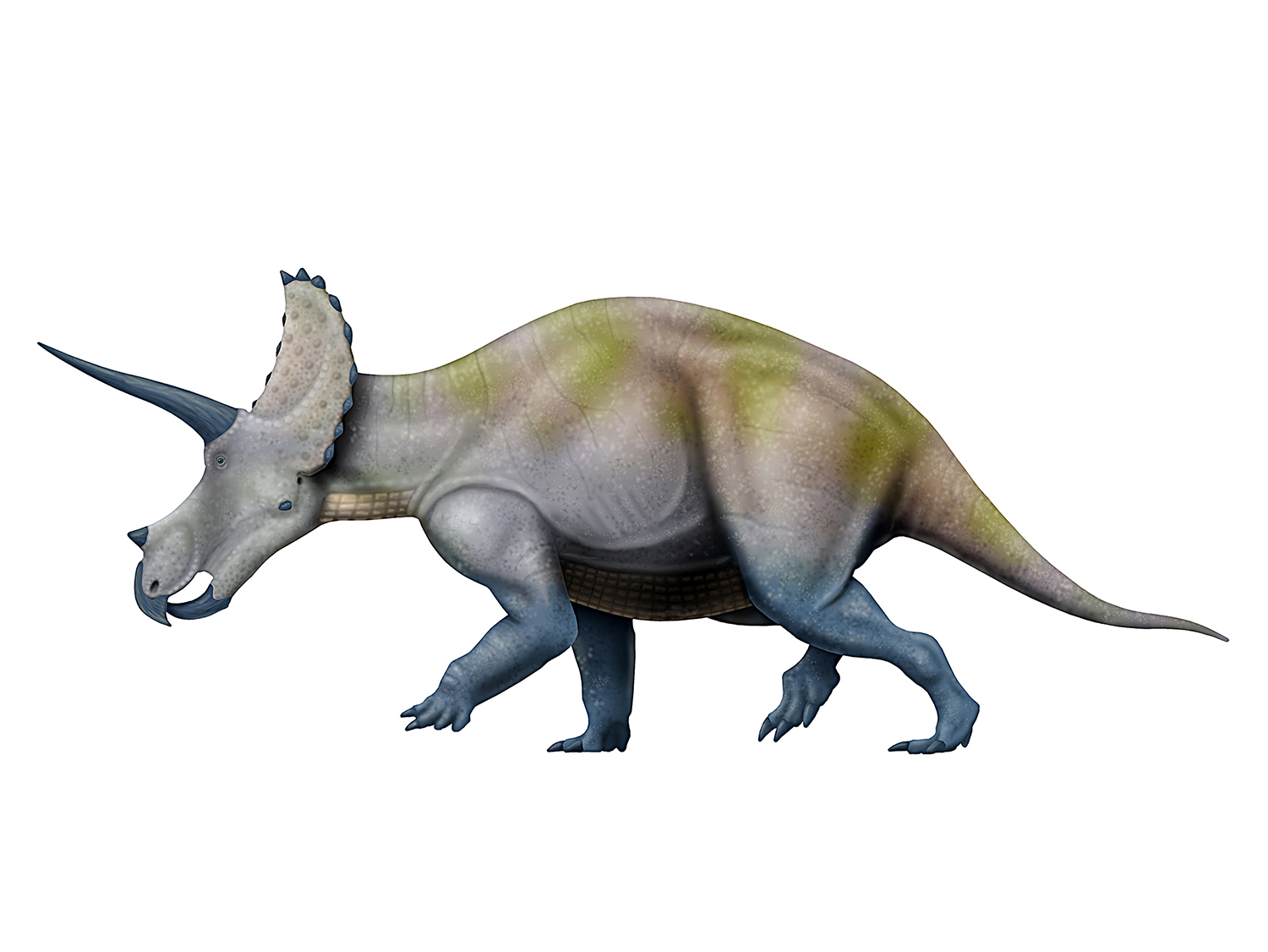

In the beginning...

Acrocanthosaurus itself is not a new dinosaur. It was described in 1950, and it was noted at the time that the specimen was a carnosaur with enlarged neural spines on the back. What really brought Acrocanthosaurus to my attention, however, was the reconstruction of NCSM 14345, the "Fran" specimen, which was prepared, molded, and mounted by Black Hills in the 1990s. One of those specimens became part of a travelling display that I contributed to, and I was inspired by the fully restored mount, as well as my ability to take lots of photographs of the mount.

Alas, that was in the "olden days" when cameras captured light on sheets impregnated with silver nitrate rather than CCDs, and I never did scan in those photos. I still had them in 2003, but they appear to be one of many casualties of moving around frequently.

I was also attending the University of Wyoming, and their Geology library had supplied valuable gifts: descriptions of Acrocanthosaurus specimens by Jerry Harris (1998), and Currie & Carpenter (2000). Armed with proto-pdfs (read: xeroxed copies), lots of photos, and an abundance of enthusiasm I sat down to create my first all-digital skeletal reconstruction.

The tomb of the unknown skeletal...

Directly above, what you don't see is my first Acrocanthosaurus skeletal. I'm not being shy, I just didn't back up the original very carefully, and eventually the hard drive it was on suffered a systemic failure. Cloud storage was a pie-in-the-sky dream at the time, so I've lost several "original" skeletal files during the course of computer failures over the years. Luckily I've been anal retentive enough to keep current versions of skeletal files on multiple hard drives, so I haven't totally lost a reconstruction (at least, not a digital one).

What I can say is that in many ways my first attempt was an unmitigated failure. For starters, I didn't actually have the papers I mentioned above in their entirety. I'd read them in Laramie, but at the end of the semester I only photocopied the parts I thought I'd need (hey, it took time and money to copy texts in those days!). And of course the photocopies didn't always do justice to the original figures.

.jpg)