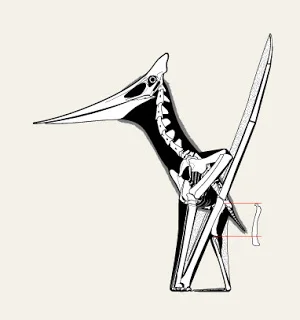

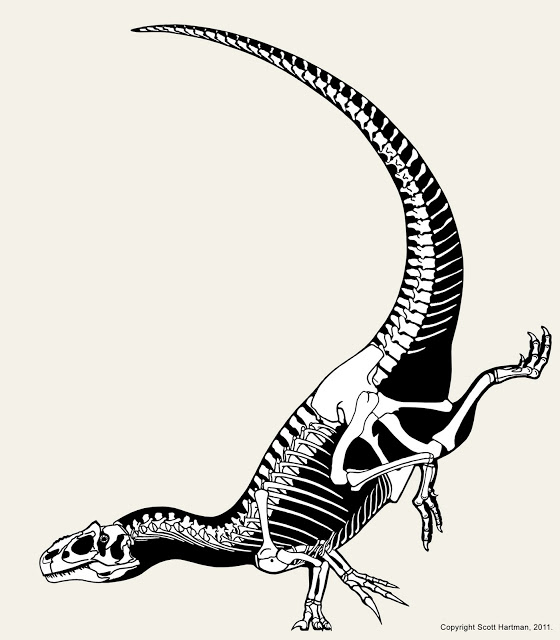

It's an impressive pose for a flying animal. A lot of people really like the look, and it lines up nicely with the same pose in birds, to which pterosaurs are often compared. There's just one (big) problem with it: pterosaurs probably never sprinted around on their hindlimbs like the reconstructions show.

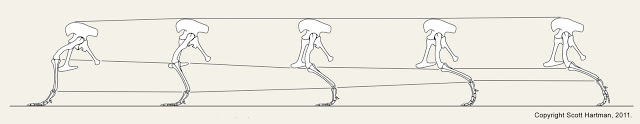

In the case of pterosaurs, the "standard running pose" is typically presented as a launch pose. However, in the late 90's, Jim Cunningham made a strong case for quadrupedal launching in Quetzalcoatlus at a series of presentations for both engineers and biologists. In 2008, I published a manuscript on a sizable comparative study I ran on bone structural strength estimates in the forelimb and hindlimb, which demonstrated that most pterosaurs probably launched quadrupedally rather than bipedally.

Now, I know you're thinking "Oh c'mon, Mike, you just don't like those bipedal running pterosaurs because they conflict with your personal results. You're biased!" I may be biased in some sense, but actually, that's not the problem. I would not mind bipedal, sprinting pterosaurs if another study had used different data to support the idea. But the reality is that no analysis has ever produced support for bipedal launching in pterosaurs. In fact, so far as I am aware, my paper was the first attempt at testing between the two modes of launch. There have not been a great number of biomechanical analyses run on pterosaurs, but there were a handful back in the 1970's and again in the early 2000's. A few of these considered their performance during takeoff, and the authors all assumed a bipedal launch mechanism, as in birds. The key word there is assumed - those studies asked the question "if pterosaurs launched like birds, then how would it work out?", but they never actually tested if a bipedal run was likely. I think the first lesson here is this:

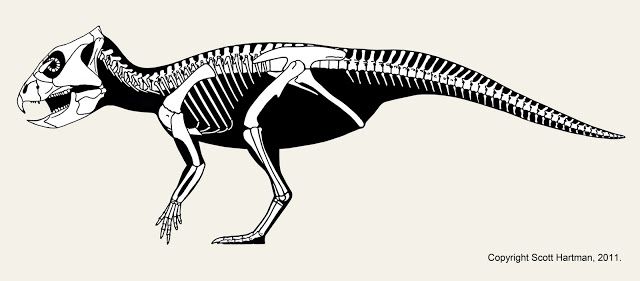

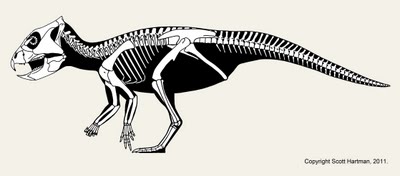

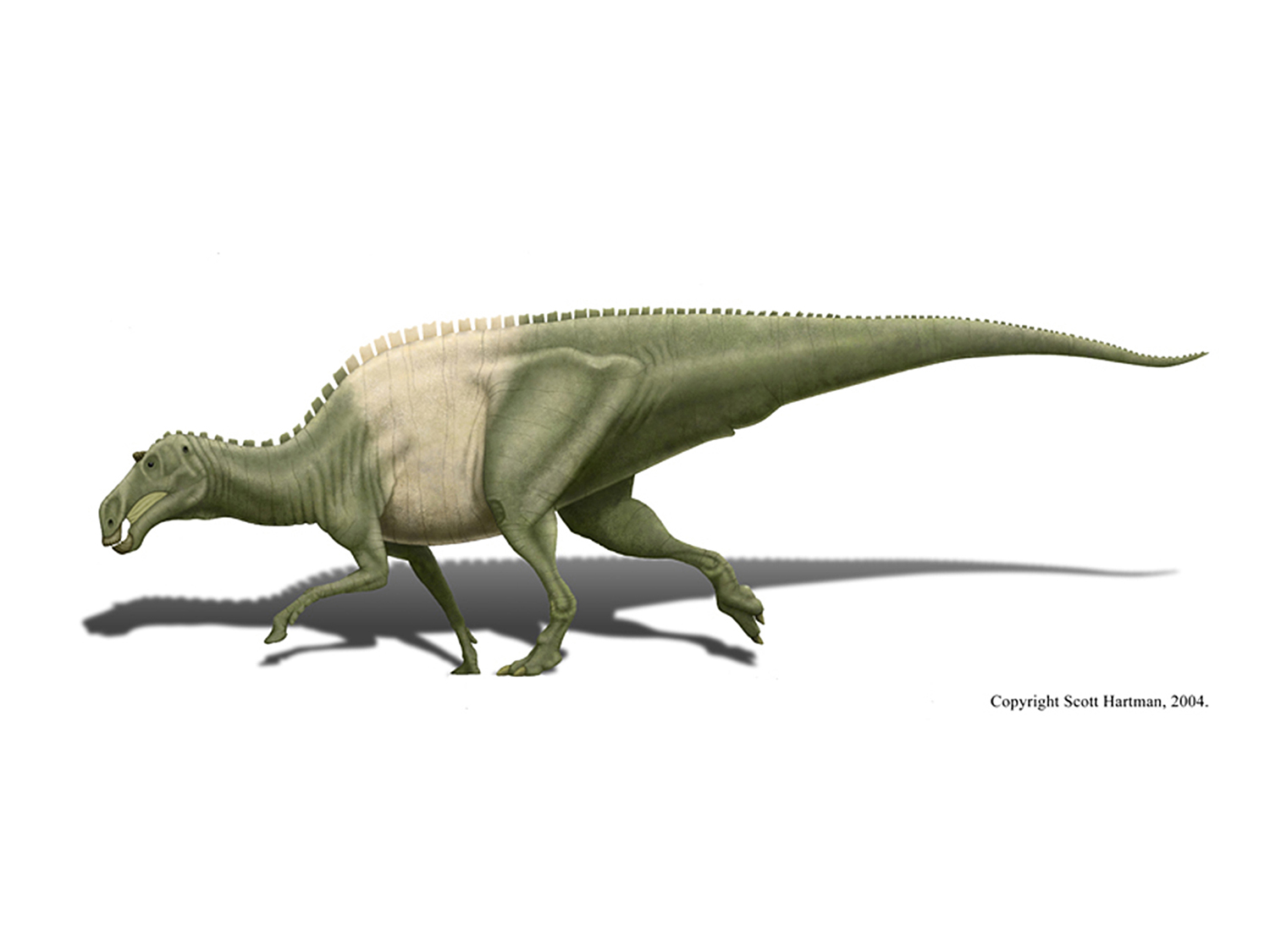

Don't reconstruct skeletal images in poses the animal was not known to reach, unless you are specifically trying to argue the plausibility in conjunction with the pose, with appropriate empirical data present.

Most viewers of a skeletal reconstruction will assume that the animal could (and did) the action shown by the skeletal pose. More discriminating viewers may consider the issue more thoroughly, but either way this gets in the way of the point of a typical reconstruction.

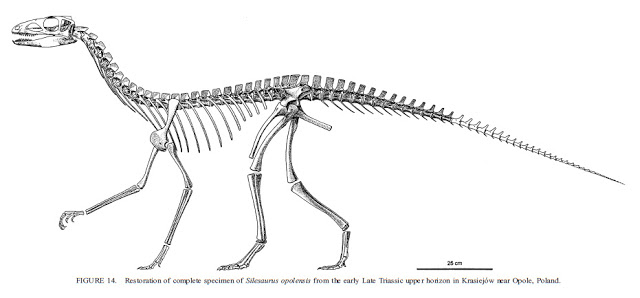

A typical skeletal is supposed to show off the anatomy. If the paper you are illustrating happens to be arguing for a specific dynamic action, then it makes sense to show the animal in that pose. If there is a dynamic pose that others have shown to be plausible, then that's fine, too - but not as a standard pose, because there will nearly always be some animal that you come across later that can't do it. Nearly all terrestrial vertebrates can manage a slow walk, but only some can sprint - so choosing sprinting as your standard is risky. Inevitably, something is going to end up sprinting in your illustrations that never did so in life.

We can make an animal do anything we want in an illustration. Scott made an Allosaurus do a handstand. We could make Quetzalcoatlus launch by vaulting on its beak. These extreme examples are obvious, but less extreme cases can be difficult to detect. The ability to render a good illustration is powerful, because it can make the action or anatomy suggested by the image seem plausible, even if it's completely false or fabricated. If you're an illustrator, use your powers wisely.

Where Does that Wing Go?

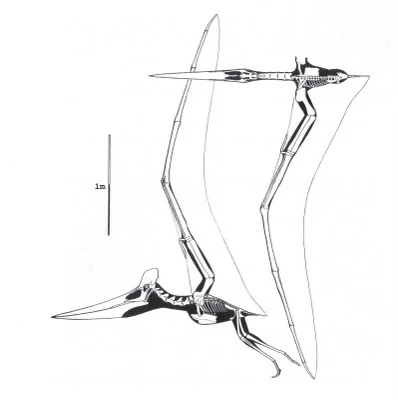

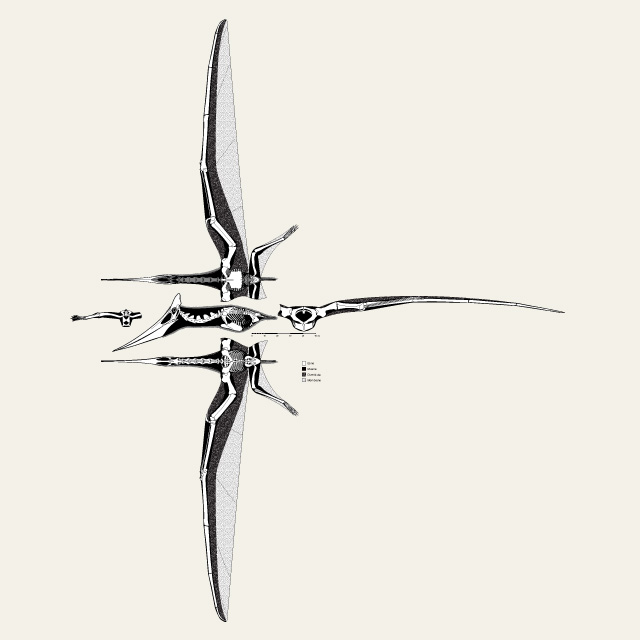

One really tricky issue with pterosaurs is the wings - we don't know for certain where the wings attached in most species, and even if we pick a particular attachment point, there are a range of potential resulting wing shapes (if you want to read more about this issue, check out the section on flight over at pterosaur.net).