The hadrosaur repose of 2018

/Long-time dinosaur skeletal fans may recall that I undertook a long-term project of reposing all of my skeletals back in 2011. That year I managed to update all of my bipedal skeletals (theropods, “prosauropods” and some of the runtier ornithischians). In 2014 I followed that up by reposing and updating all of my sauropod skeletals. My armored dinosaur skeletals have gotten pose updates in a piecemeal fashion, but today I’m unveiling another major overhaul: Hadrosaurs.

The shoulder bone (scapula) of Leonardo the ‘mummified’ hadrosaur is clearly about halfway up the rib cage, not up near the top. Image courtesy of Red Rocket Photography/The Children’s Museum of Indianapolis/Wikimedia Commons.

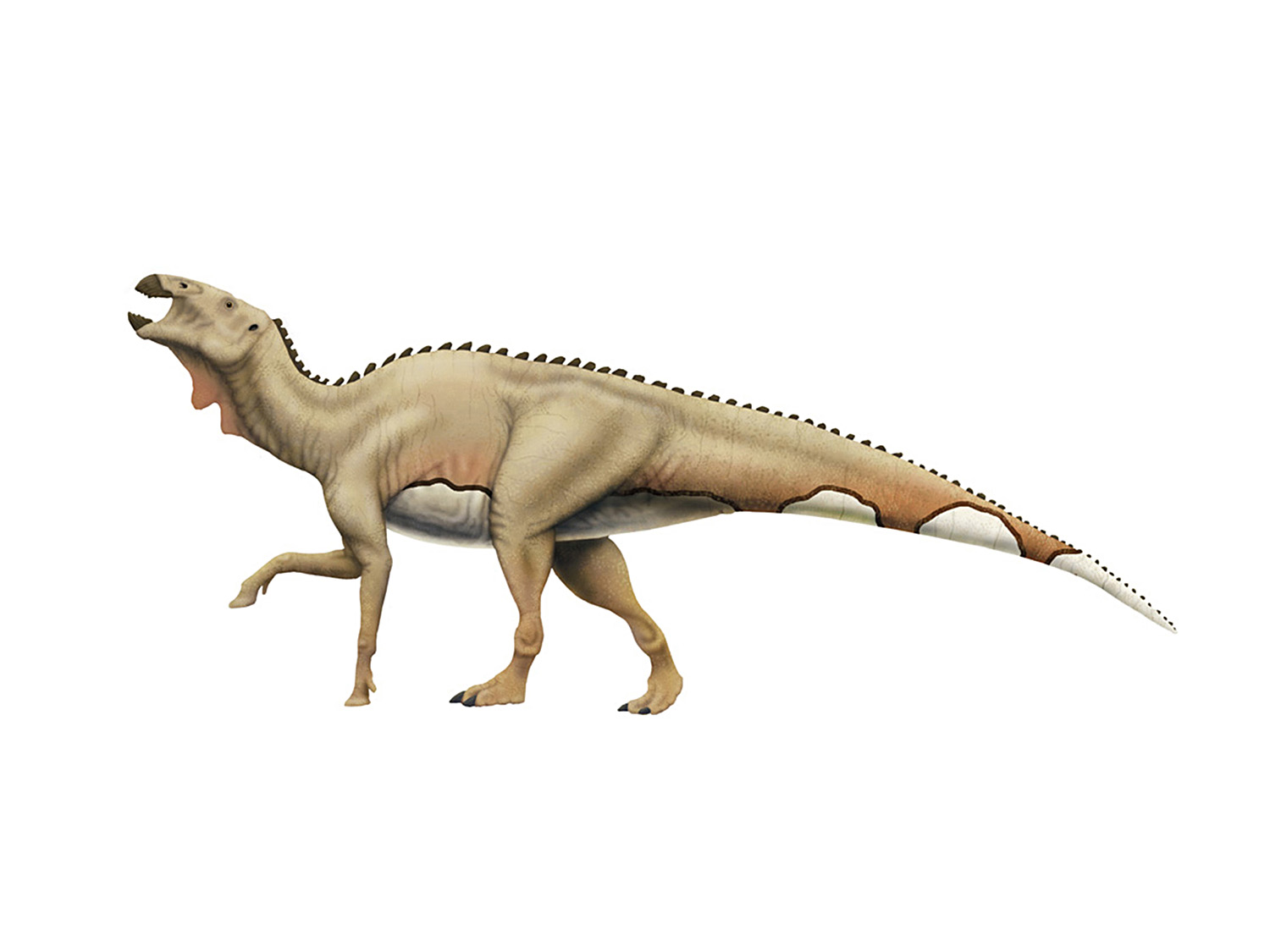

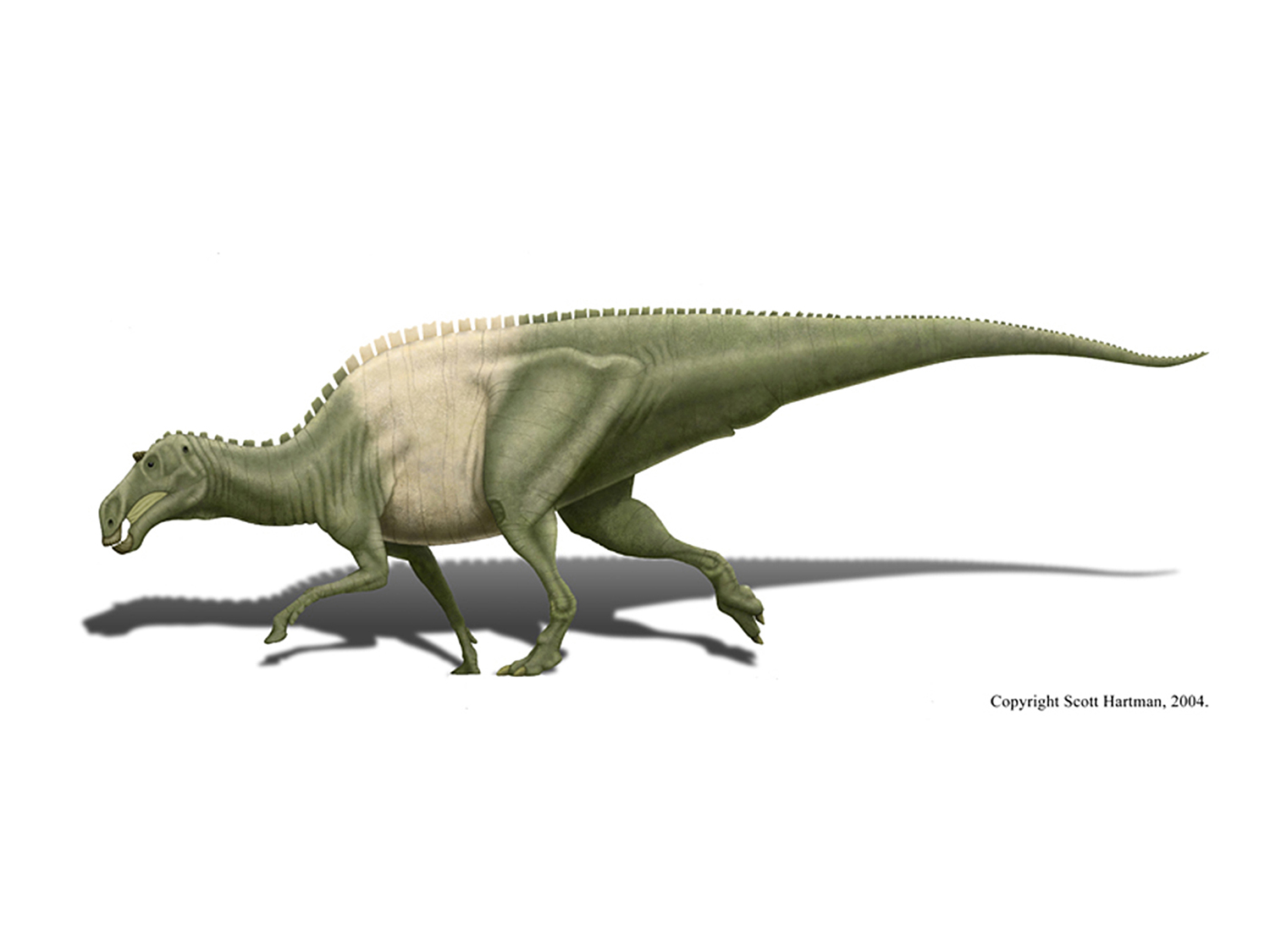

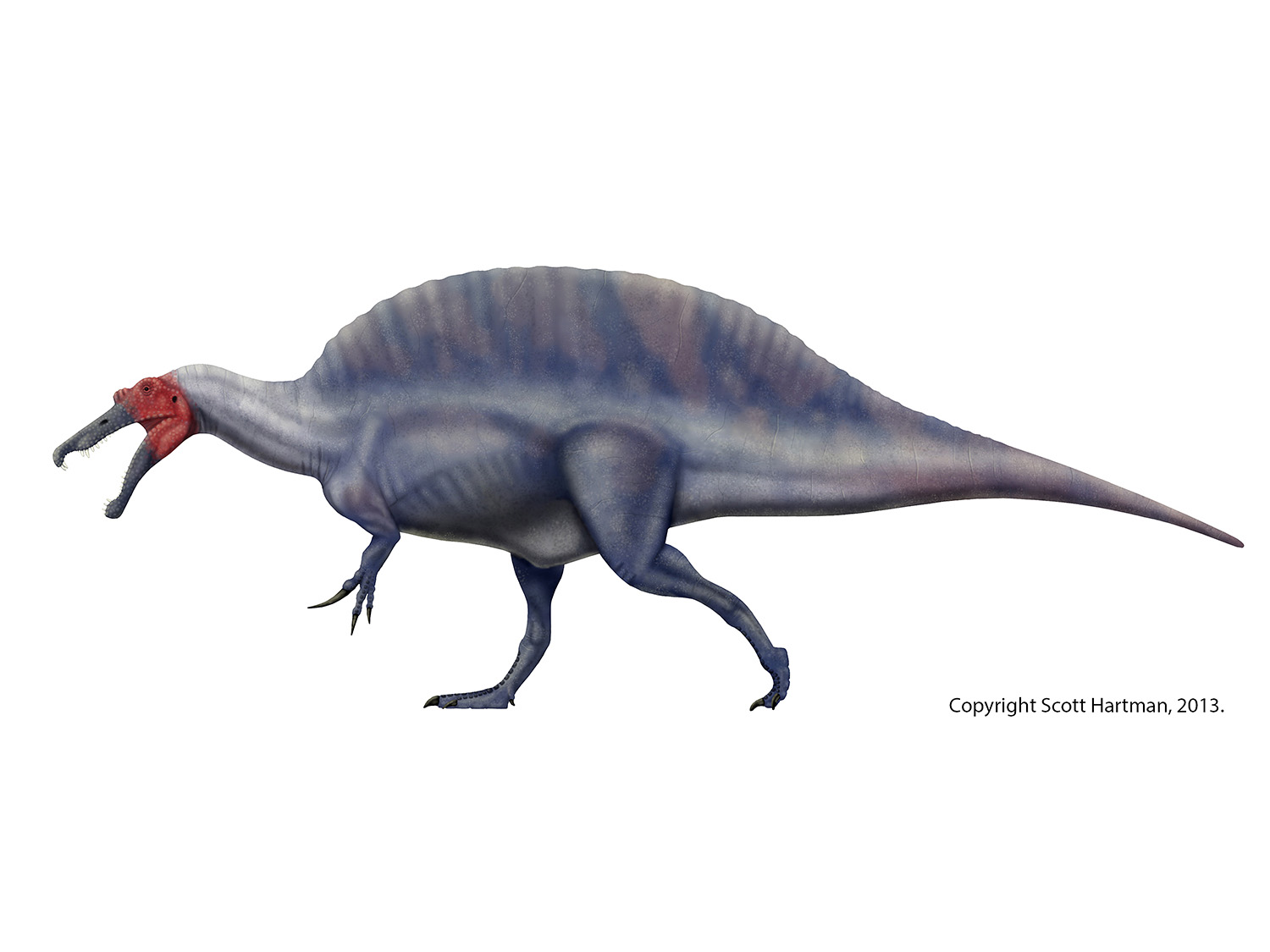

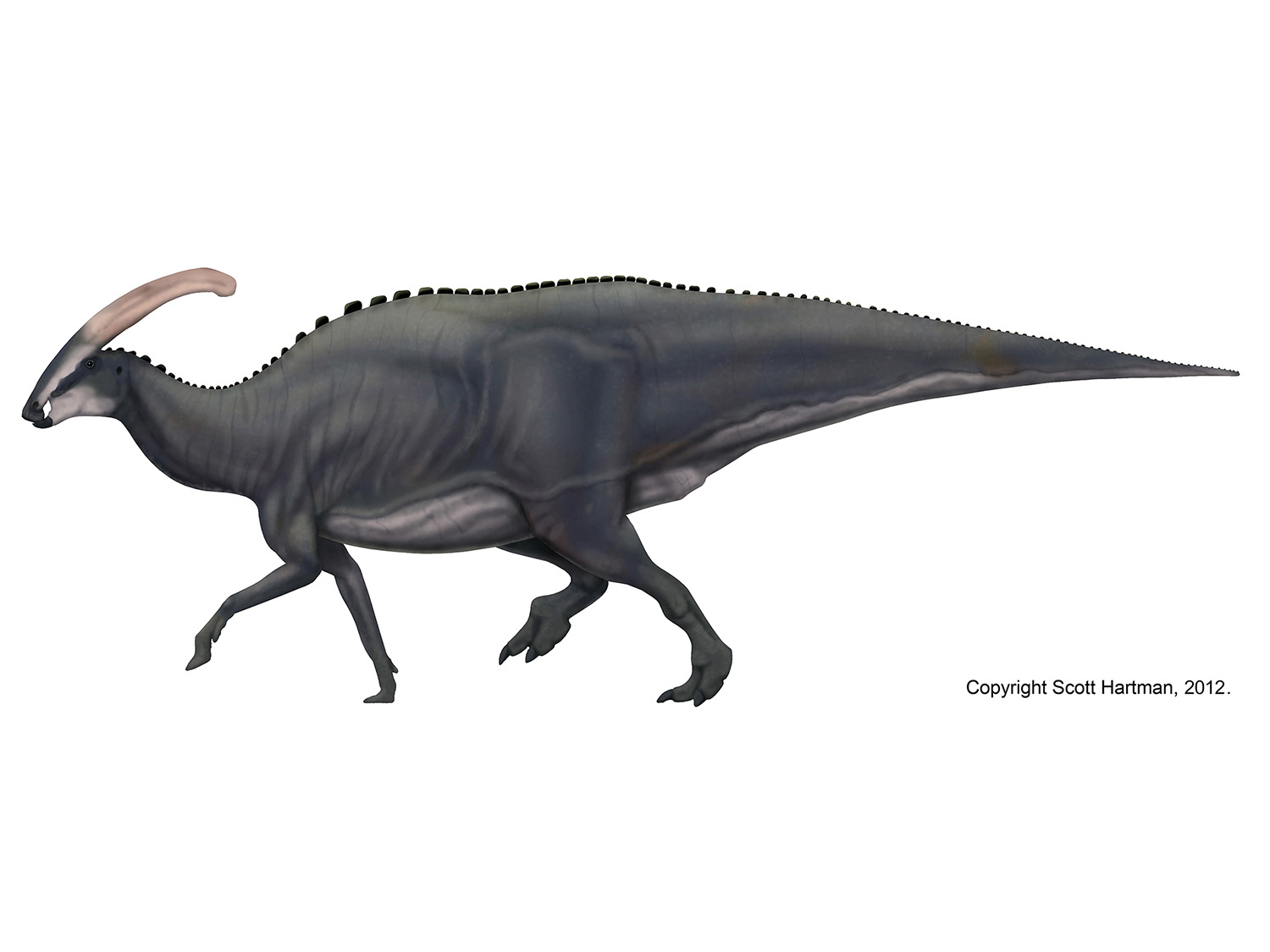

I don’t have as many hadrosaurs skeletals as some other groups of dinosaurs, but there was quite a bit to do for each skeletal. In addition to modifying the gait to more of a sedate walk pose (from the more hustling one I’d adopted from Greg Paul decades ago), there were major anatomical and stance changes that needed to be made. For starters, I’d been illustrating the forelimbs with too much pronation. Both articulated specimens and hadrosaur trackways show that the ‘palms’ faced more inward (somewhere around 45 degrees) rather than facing backwards, as in most quadrupedal mammals. This meant redrawing the hands, wrists, and lower arm bones (ulna and radius) for each specimen.

But the changes didn’t stop there! Many of my older skeletals (prior to 2014) also had the pectoral girdle placement and orientation subtle wrong. Fixing this wasn’t as simple as moving the pectoral girdle, as the change impacts the entire orientation of the body. Because the forelimbs can’t move down any lower (they’re already on the ground!) changing their relative position forces the torso to tilt up, and like a teeter-totter the tail has to tilt down at the same time. That turns out to be a very good thing for functional reasons (I’ll have more to say on that soon), but it also means having to overhaul almost the entire skeletal.

Here’s an example of how that looks with Parasaurolophus cyrtocristatus:

Depending on the age of the skeletal several other smaller updates were also done - keratinous upper beaks have been extended to match recent discoveries, tendon thickness was increased, and tails have become more heavily muscled. The updated hadrosaur skeletals are now live in the Ornithischian Skeletal Gallery, if you want to take a look.